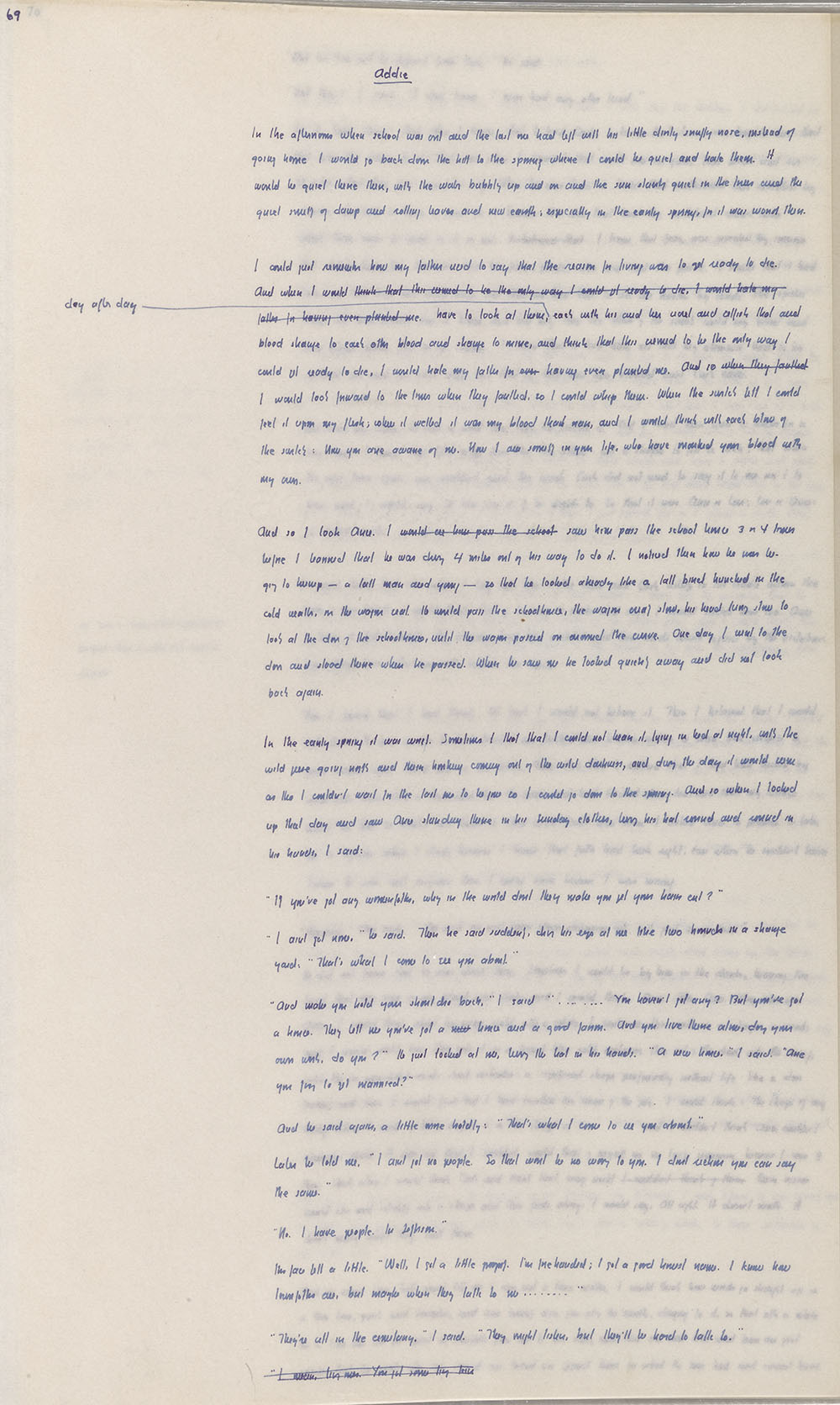

TRANSCRIPTION

Addie

In the afternoon when school was out and the last one had left with his little dirty snuffy nose, instead of

going home I would go back down the hill to the spring where I could be quiet and hate them. It

would be quiet there then, with the water bubbling up and on and the sun slanting quiet in the trees and the

quiet smell of damp and rotting leaves and new earth; especially in the early spring, for it was worst then.

I could just remember how my father used to say that the reason for living was to get ready to die.

And when I would <think that this seemed to be the only way I could get ready to die, I would hate my

father for having ever planted me.> have to look at them,

[margin: day after day]

each with his and her secret and selfish thot and

blood strange to each other blood and strange to mine, and think that this seemed to be the only way I

could get ready to die, I would hate my father for <ever> having ever planted me. And so <when they faulted>

I would look forward to the times when they faulted, so I could whip them. When the switch fell I could

feel it upon my flesh; when it welted it was my blood that ran, and I would think with each blow of

the switch: Now you are aware of me. Now I am something in your life, who have marked your blood with

my own.

And so I took Anse. I <would see him pass the school> saw him pass the school house 3 or 4 times

before I learned that he was driving 4 miles out of his way to do it. I noticed then how he was be-

ginning to hump – a tall man and young – so that he looked already like a tall bird hunched in the

cold weather, on the wagon seat. He would pass the school house, the wagon creaking slow, his head turning slow to

look at the door of the school house, until the wagon passed on around the curve. One day I went to the

door and stood there when he passed. When he saw me he looked quickly away and did not look

back again.

In the early spring it was worst. Sometimes I thot that I could not bear it, lying in bed at night, with the

wild geese going north and their honking coming out of the wild darkness, and during the day it would seem

as tho I couldn't wait for the last ones to be gone so I could go down to the spring. And so when I looked

up that day and saw Anse standing there in his Sunday clothes, turning his hat round and round in

his hands, I said:

"If you've got any womenfolks, why in the world dont they make you get your hair cut?"

"I aint got none," he said. Then he said suddenly, driving his eyes at me like two hounds in a strange

yard. "That's what I come to see you about."

"And make you hold your shoulders back," I said. ". . . . . . . . You haven't got any? But you've got

a house. They tell me you've got a <new> house and a good farm. And you live there alone, doing your

own wash, do you?" He just looked at me, turning the hat in his hands. "A new house," I said. "Are

you going to get married?"

And he said again, a little more boldly: "That's what I come to see you about."

Later he told me, "I aint got no people. So that wont be no worry to you. I dont reckon you can say

the same."

"No. I have people. In Jefferson."

His face fell a little. "Well, I got a little property. I'm forehanded; I got a good honest name. I know how

townfolks are, but maybe when they talk to me . . . . . . . ."

"They're all in the cemetary," I said. "They might listen, but they'll be hard to talk to."

<"I mean, living ones. You got some living [folks?]>

|