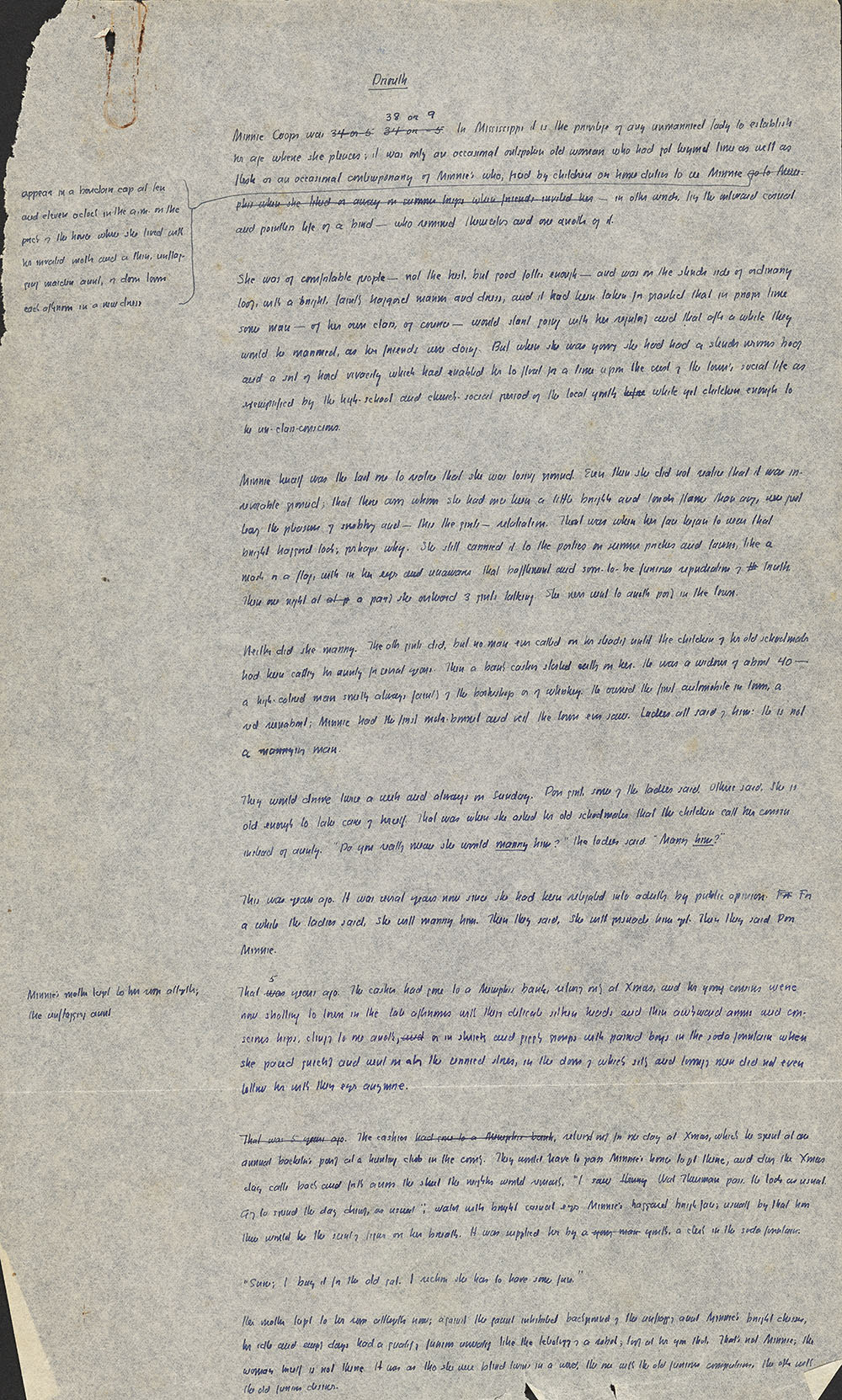

TRANSCRIPTION

Drouth

Minnie Cooper was <34 or 5> <34 or -5> 38 or 9. In Mississippi it is the privilege of any unmarried lady to establish

her age where she pleases; it was only an occasional outspoken old woman who had got beyond time as well as

flesh or an occasional contemporary of Minnie's who, [forced?] by children or home duties to see Minnie

[margin: appear in a boudoir cap at ten and eleven oclock in the a.m. on the porch of the house where she lived with her invalid mother and a thin, unflagging maiden aunt, or down town each afternoon in a new dress]

<go to Mem-

phis when she liked or away on summer trips when friends invited her> – in other words, living the awkward casual

and pointless life of a bird – who reminded themselves and one another of it.

She was of comfortable people – not the best, but good folks enough – and was on the slender side of ordinary

looks, with a bright, faintly haggard manner and dress, and it had been taken for granted that in proper time

some man – of her own class, of course – would start going with her regularly and that after a while they

would be married, as her friends were doing. But when she was young she had had a slender nervous body

and a sort of hard vivacity which had enabled her to float for a time upon the crest of the town's social life as

exemplified by the high-school and church-social period of the local youths <before> while yet children enough to

be un-class-conscious.

Minnie herself was the last one to realize that she was losing ground. Even then she did not realize that it was ir-

recoverable ground; that those among whom she had once been a little brighter and louder flame than any, were just

learning the pleasures of snobbery and – this the girls – retaliation. That was when her face began to wear that

bright haggard look; perhaps why. She still carried it to the parties on summer porches and lawns, like a

mask or a flag, with in her eyes and unawares that bafflement and soon-to-be furious repudiation of <th> truth.

Then one night at <at p> a party she overheard 3 girls talking. She never went to another party in the town.

Neither did she marry. The other girls did, but no man ever called on her steadily until the children of her old schoolmates

had been calling her aunty for several years. Then a bank cashier started calling on her. He was a widower of about forty–

a high-colored man smelling always faintly of the barbershop or of whiskey. He owned the first automobile in town, a

red runabout; Minnie had the first motor-bonnet and veil the town ever saw. Ladies all said of him: He is not a marrying man.

They would drive twice a week and always on Sunday. Poor girl, some of the ladies said. Others said, She is

old enough to take care of herself. That was when she asked her old schoolmates that the children call her cousin

instead of aunty. "Do you really mean she would marry him" the ladies said. "Marry him?"

This was years ago. It was several years now since she had been relegated into adultery by public opinion. <For> For

a while the ladies said, She will marry him. Then they said, She will persuade him yet. Then they said Poor

Minnie.

[margin: Minnie's mother kept to her room altogether; the unflagging aunt]

That <was> 5 years ago. The cashier had gone to a Memphis bank, returning only at Xmas, and her young cousins were

now strolling to town in the late afternoons with their delicate silken heads and their awkward arms and con-

scious hips, clinging to one another, <and> or in shrieks and giggling groups with paired boys in the soda fountain when

she [passed?] quickly and went on along the serried stores, in the doors of which sitting and lounging men did not even

follow her with their eyes any more.

<That was 5 years ago.> The cashier <had gone to a Memphis bank,> returned only for one day at Xmas, which he spent at an

annual bachelor's party at a hunting club in the county. They would have to pass Minnie's home to get there, and during the Xmas

day calls back and forth across the street their neighbors would remark, "I saw <Henry> Wat Thurman pass. He looks as usual.

Going to spend the day drinking, as usual," watching with bright casual eyes Minnie's haggard [bright?] face; usually by that hour

there would be the scent of liquor on her breath. It was supplied her by a <young man> youth, a clerk in the soda fountain:

"Sure; I buy it for the old gal. I reckon she has to have some fun."

Her mother kept to her room alltogether now; against the gaunt inhibited background of the unflagging aunt Minnie's bright dresses,

her idle and empty days had a quality of furious unreality like the teleology of a robot; looking at her you thought, That's not Minnie; the

woman herself is not there. It was as tho she were blind twins in a [wood?], the one with the old furious compulsions, the other with

the old furious desires.

|