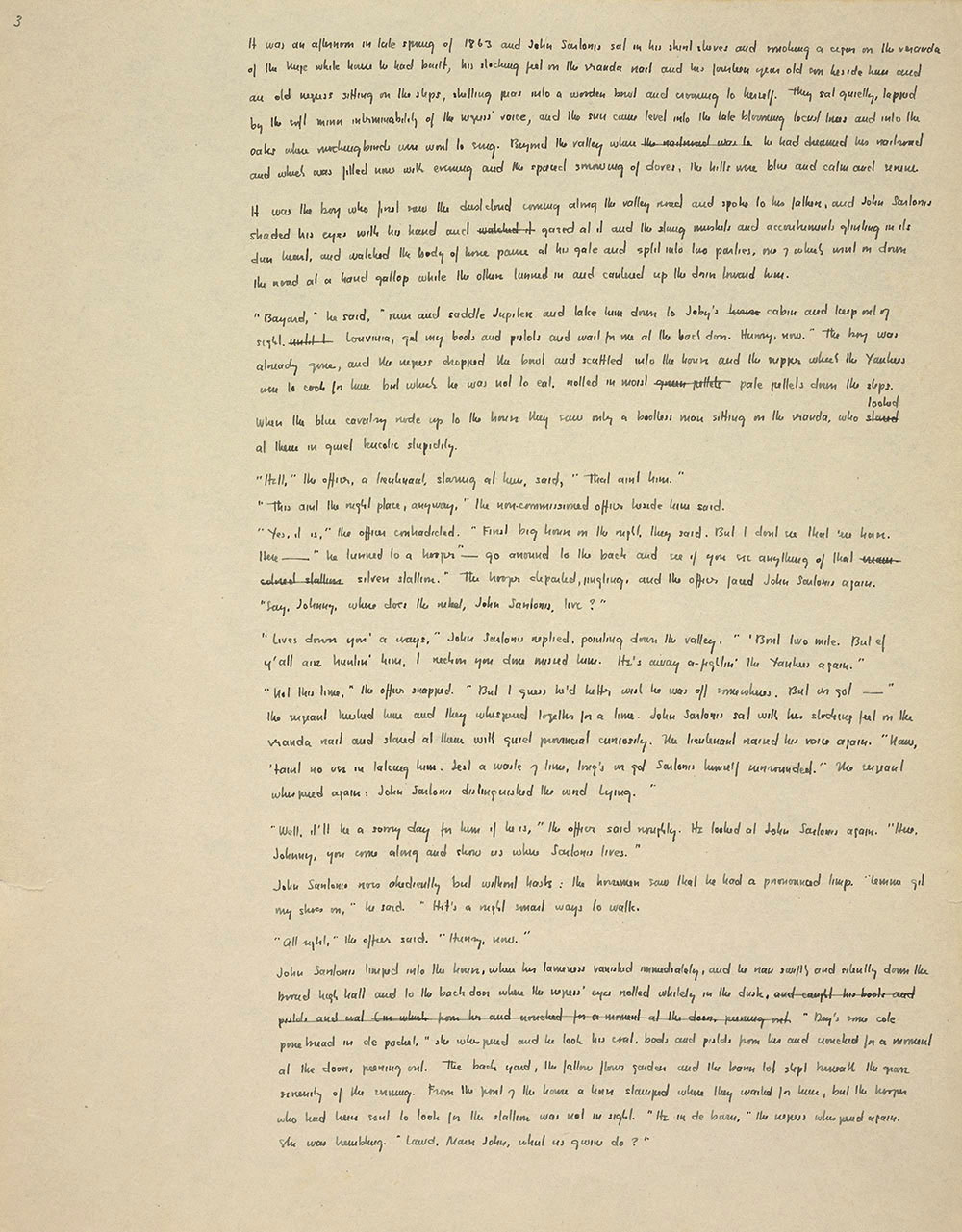

TRANSCRIPTION

It was an afternoon in the late spring of 1863 and John Sartoris sat in his shirt sleeves and smoking a cigar on the veranda

of the huge white house he had built, his stocking feet on the veranda rail and his fourteen year old son beside him and

an old negress sitting on the steps, shelling peas into a wooden bowl and crooning to herself. They sat quietly, lapped

by the soft minor interminability of the negress' voice, and the sun came level into the late blooming locust trees and into the

oaks where mockingbirds were wont to sing. Beyond the valley where <the railroad was to> he had dreamed his railroad

and which was filled now with evening and the [spaced?] sorrowing of doves, the hills were blue and calm and serene.

It was the boy who first saw the dust cloud coming along the valley road and spoke to his father, and John Sartoris

shaded his eyes with his hand and <watched it> gazed at it and the slung muskets and accoutrements glinting in its

dun heart, and watched the body of horse pause at his gate and split into the parties, one of which went on down

the road at a hard gallop while the other turned in and cantered up the drive toward him.

"Bayard," he said, "run and saddle Jupiter and take him down to Joby's <house> cabin and keep out of

sight. <until I> Louvinia, get my boots and pistols and wait for me at the back door. Hurry, now." The boy was

already gone, and the negress dropped the bowl and scuffled into the house and the supper which the Yankees

were to cook for him but which he was not to eat, rolled in moist <green pellets> pale pellets down steps.

When the blue cavalry rode up to the house they saw only a bootless man sitting on the veranda, who <stared> looked

at them in quiet bucolic stupidity.

"Hell," the officer, a lieutenant, staring at him, said, "That aint him."

"This aint the right place, anyway," the non-commissioned officer beside him said.

"Yes, it is," the officer contradicted. "First big house on the right, they said. But I dont see that 'ere horse.

Here — " he turned to a trooper " — go around to the back and see if you see anything of that <cream-

colored stallion> silver stallion." The trooper departed, jingling, and the officer faced John Sartoris again. "Say, Johnny, where does the rebel, John Sartoris, live?"

"Lives down yon' a ways," John Sartoris replied, pointing down the valley. "'Bout two mile. But ef

y'all are huntin' him, I reckon you done missed him. He's away a-fightin' the Yankees again."

"Not this time," the officer snapped. "But I guess he'd better wish he was off somewheres. But [we got?] — "

the sergeant hushed him and they whispered together for a time. John Sartoris sat with his slouching feet on the

veranda rail and stared at them with quiet provincial curiosity. The lieutenant raised his voice again. "Naw,

'taint no use in taking him. Jest a waste of time, long's we got Sartoris himself surrounded." The sergeant

whispered again: John Sartoris distinguished the word lying.

"Well, it'll be a sorry day for him if he is," the officer said roughly. He looked at John Sartoris again. "Here,

Johnny, you come along and show us where Sartoris lives."

John Sartoris rose obediently but without haste: the horsemen saw that he had a pronounced limp. "Lemme git

my shoes on," he said. "Hit's a right smart ways to walk.["]

"All right," the officer said. "Hurry, now."

John Sartoris limped into the house, where his lameness vanished immediately, and he ran swiftly and silently down the

broad high hall and to the back door where the negress' eyes rolled whitely in the dusk, <and caught his boots and

pistols and coat <<(in which>> from her and crouched for a moment at the door, peering out.> "Dey's some cole

pone bread in de pocket," she whispered and he took his coat, boots and pistols from her and crouched for a moment

at the door, peering out. The back yard, the fallow flower garden and the barn lot slept beneath the grave

serenity of the evening. From the front of the house a horse stamped where they waited for him, but the trooper

who had been sent to look for the stallion was not in sight. "He in de barn," the negress whispered again.

She was trembling. "Lawd, Marse John, what us gwine do?"

|