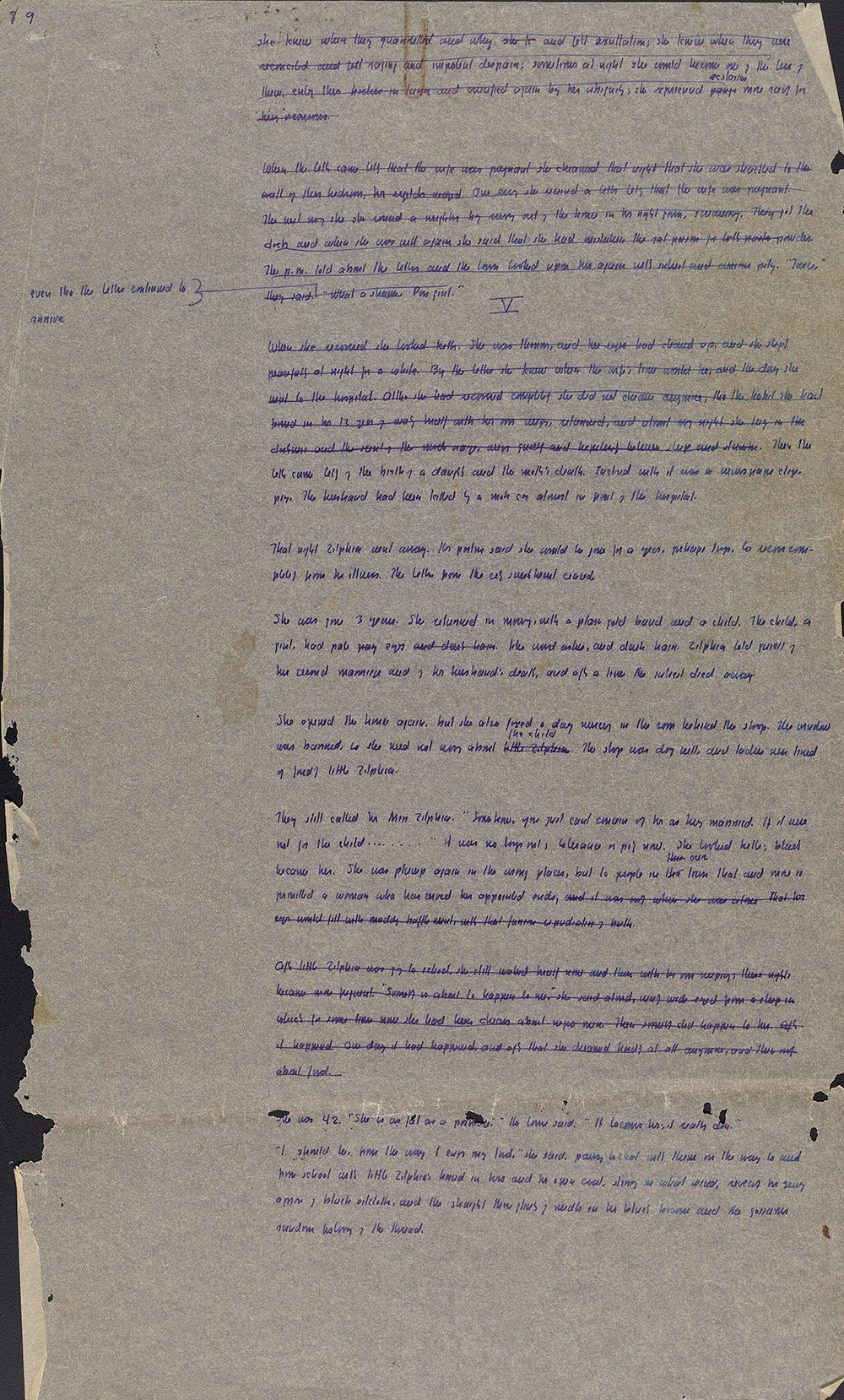

TRANSCRIPTION

<she knew when they quarrelled and why, <<she fe>> and felt exultation; she knew when they were

reconciled and felt raging and impotent despair; sometimes at night she would become one of the two of

them, entering their bodies in turn and crucified again by her virginity; she experienced <<pangs>> ecstasies more racking for

their vicariousness.>

<<When the letter came telling that the wife was pregnant she dreamed that night that she was shackled to the

wall of their bedroom, her eyelids [wedged?].>> <One evening she received a letter telling that the wife was pregnant.

The next morning she she waked a neighbor by running out of the house in her night gown, screaming. They got the

doctor and when she was well again she said that she had mistaken the rat poison for tooth paste powder.

The p.m. told about the letters and the town looked upon her again with interest and curious pity. "Twice,"

they said.

[margin: even though the letters continued to arrive]

What a shame. Poor girl.">

V

<When she recovered she looked better. She was thinner and her eyes had cleared up, and she slept

peacefully at night for a while. By the letters she knew when the wife's time would be, and the day she

went to the hospital. Although she had recovered completely she did not dream anymore, though the habit she

formed in her 12 years of waking herself with her own weeping, returned, and almost every night she lay in the

darkness and the scent of the mock orange, weeping quietly and hopelessly between sleep and slumber.> Then the

letter came telling of the birth of a daughter and the mother's death. Enclosed with it was a newspaper clip-

ping. The husband had been killed by a motor car almost in front of the hospital.

That night Zilphia went away. Her partner said she would be gone for a year, perhaps longer, to recover com-

pletely from her illness. The letters from the city sweetheart ceased.

She was gone 3 years. She returned in mourning, with a plain gold band and a child. The child, a

girl, had pale <gray> eyes <and dark hair.> like wood ashes, and dark hair. Zilphia told quietly of

her second marriage and of her husband's death, and after a time the interest died away.

She opened the house again, but she also fixed a day nursery in the room behind the shop. The window

was barred, so she need not worry about <little Zilphia> the child. The shop was doing well, and ladies never tired

of fondling little Zilphia.

They still called her Miss Zilphia. "Somehow, you just cant conceive of her as being married. If it were

not for the child . . . . . . . . " It was no longer out of tolerance or pity now. She looked better; black

became her. She was plump again in the wrong places, but to people in <the> <this> our town that and more is

permitted a woman who has served her appointed ends, <and it was only when she was alone that her

eyes would fill with muddy bafflement, with that furious repudiation of birth.>

<After little Zilphia was going to school, she still waked herself now and then with her own weeping; these nights

became more frequent. "Something is about to happen to me," she said aloud, waking wide-eyed from a sleep in

which for some time now she had been dreaming about negro men. Then something did happen to her. <<After

it happened.>> One day it had happened, and after that she dreamed hardly at all anymore, and then only

about food.>

She was 42. "She is as fat as a partridge," the town said. "It becomes her; it really does."

"I should be, from the way I enjoy my food," she said, pausing to chat with them on the way to and

from school with little Zilphia's hand in hers and her open coat, stirring in [what?] wind, revealing her sewing

apron of black oilcloth, and the staight thin glints of needles in her black bosom and the gossamer

random festooning of the thread.

|