|

CLOSE WINDOW |

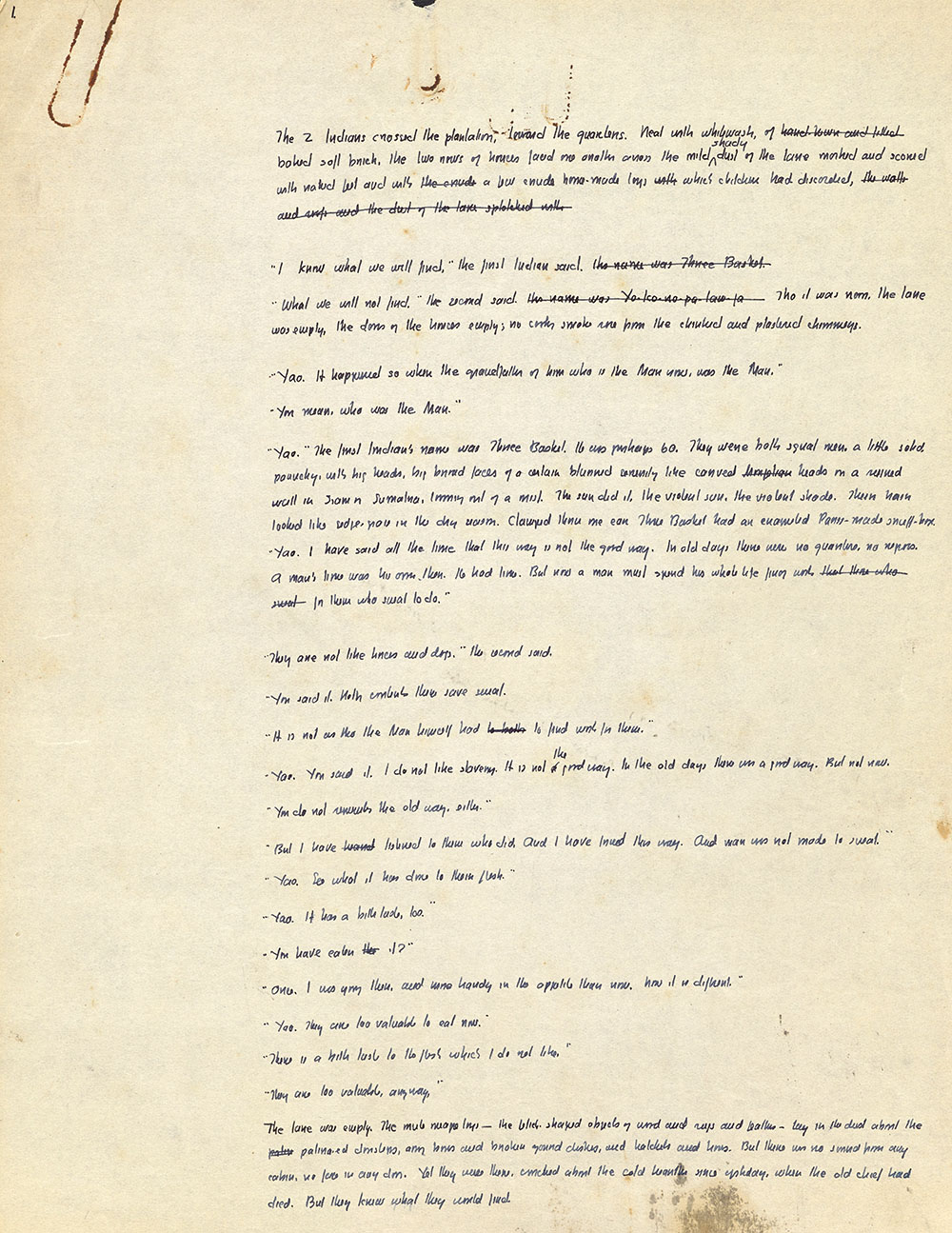

William Faulkner Foundation Collection, 1918-1959, Accession #6074 to 6074-d, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va. [Item Metadata: Autograph manuscript, 12 p. (12 R, 0 V) on 12 l.] |

|

The 2 Indians crossed the plantation, toward the quarters. Neat with whitewash, of <hand-hewn and fitted> "I know what we will find," the first Indian said. <His name was Three Basket.> "What we will not find," the second said. <His name was Yo-ko-no-pa-taw-fa> Tho it was noon, the lane "Yao. It happened so when the grandfather of him who is the Man now, was the Man." "You mean, who was the Man." "Yao." The first Indian's name was Three Basket. He was perhaps 60. They were both squat men, a little solid, "They are not like horses and dogs," the second said. "You said it. Nothing contents them save sweat. "It is not as tho the Man himself had <to bother> to find work for them." "Yao. You said it. I do not like slavery. It is not <a> the good way. In the old days there was a good way. But not now. "You do not remember the old way, either." "But I have <heard> listened to them who did. And I have [lived?] this way. And man was not made to sweat." "Yao. See what it has done to their flesh." "Yao. It has a bitter taste, too." "You have eaten <the> it?" "Once. I was young then, and more hardy in the appetite than now. Now it is different." "Yao. They are too valuable to eat now." "There is a bitter taste to the flesh which I do not like." "They are too valuable, any way." The lane was empty. The mute meagre toys - the fetich-shaped objects of wood and rags and feathers - lay in the dust about the |