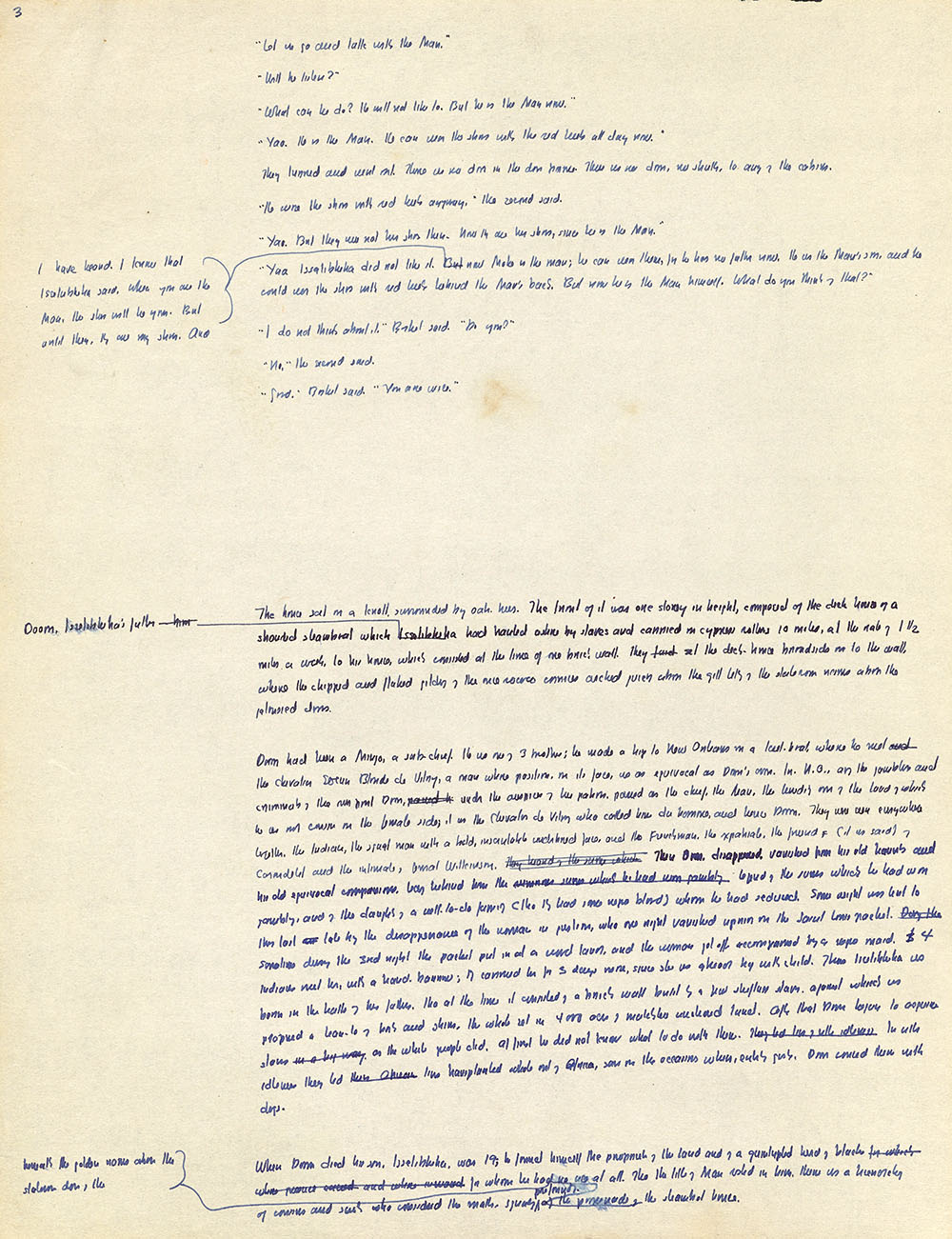

TRANSCRIPTION

"Let us go and talk with the Man."

"Will he listen?"

"What can he do? He will not like to. But he is the Man now."

"Yao. He is the Man. He can wear the shoes with the red heels all day now."

They turned and went out. There was no door in the door frame. There was no door, no [shutter?], to any of the cabins.

"He wore the shoes with red heels anyway," the second said.

"Yao. But they were not his shoes then. Now they are his shoes, since he is the Man."

"Yao. Issetibbeha did not like it.

[margin: I have heard. I know that Issetibbeha said, When you are the Man, the shoes will be yours. But until then, they are my shoes. And]

<But> now Moke is the Man; he can wear them, for he has no father now. He was the Man's son, and he

could wear the shoes with red heels behind the Man's back. But now he is the Man himself. What do you think of that?"

"I do not think about it," Basket said. "Do you?"

"No," the second said.

"Good," Basket said. "You are wise."

The house sat on a knoll, surrounded by oak trees. The front of it was one story in height, composed of the deck house of a

stranded steamboat which

[margin: Doom, Issetibbeha's father - <him>]

<Issetibbeha> had hauled ashore by slaves and carried on cypress rollers 10 miles, at the rate of 1 1/2

miles a week, to his house, which consisted at the time of one brick wall. They <laid> set the deck-house broadside on to the wall,

where the chipped and flaked gilding of the once rococo cornices cracked [quietly?] above the gilt lettering of the stateroom names above the

jalousied doors.

Doom had been a Mingo, a sub-chief. He was one of 3 brothers; he made a trip to New Orleans on a keel-boat, where he met <and>

the Chevalier Soeur Blonde de Vitry, a man whose position, on its face, was as equivocal as Doom's own. In N.O., among the gamblers and

criminals of the river front Doom, <[passed illegible]> under the auspices of his patron, passed as the chief, the Man, the hereditary owner of the land of which

he was [illegible] on the female side; it was the Chevalier de Vitry who called him du homme, and hence Doom. They were seen everywhere

together, the Indian, the squat man with a bold, inscrutable underbred face, and the Frenchman, the expatriate, the friend <of> (it was said) of

Carondelet and the intimate of General Wilkinson. <They heard of the [illegible]> Then Doom disappeared, vanished from his old haunts and

his old equivocal companions, leaving behind him the <[enormous?] sums which he had won gambling> legend of the sums which he had won

gambling, and of the daughter of a well-to-do family (tho they had some negro blood) whom he had seduced. Some weight was lent to

this last <[illegible]> tale by the disappearance of the women in question, who one night vanished up river on the Saint Louis packet. <During the>

Sometime during the 3rd night the packet put in at a wood landing, and the woman got off accompanied by a negro maid. <3> 4

Indians met her, with a hand-barrow; they carried her for 3 days [illegible], since she was already big with child. Thus Issetibbeha was

born in the halls of his father, tho at the time it consisted of a brick wall built by a few shiftless slaves, against which was

propped a lean-to of bark and skins, the whole set in 4000 acres of matchless uncleared land. After that Doom began to acquire

slaves <in a big way> as the white people did. At first he did not know what to do with them. <They led lives of utter idleness> In utter

idleness they led <their African> lives transplanted whole out of Africa, save on the occasions when, entertaining guests, Doom coursed them with

dogs.

When Doom died his son, Issetibbeha, was 19; he found himself the proprietor of the land and of a quintupled herd of blacks <for which

whose presence succeed and whose [illegible]> for whom he had no use at all. Tho the title of Man rested on him, there was a hierarchy

of cousins and such who considered the matter, squatting profoundly <on the prominade of>

[margin: beneath the golden names above the stateroom doors of the]

the steamboat house.

|