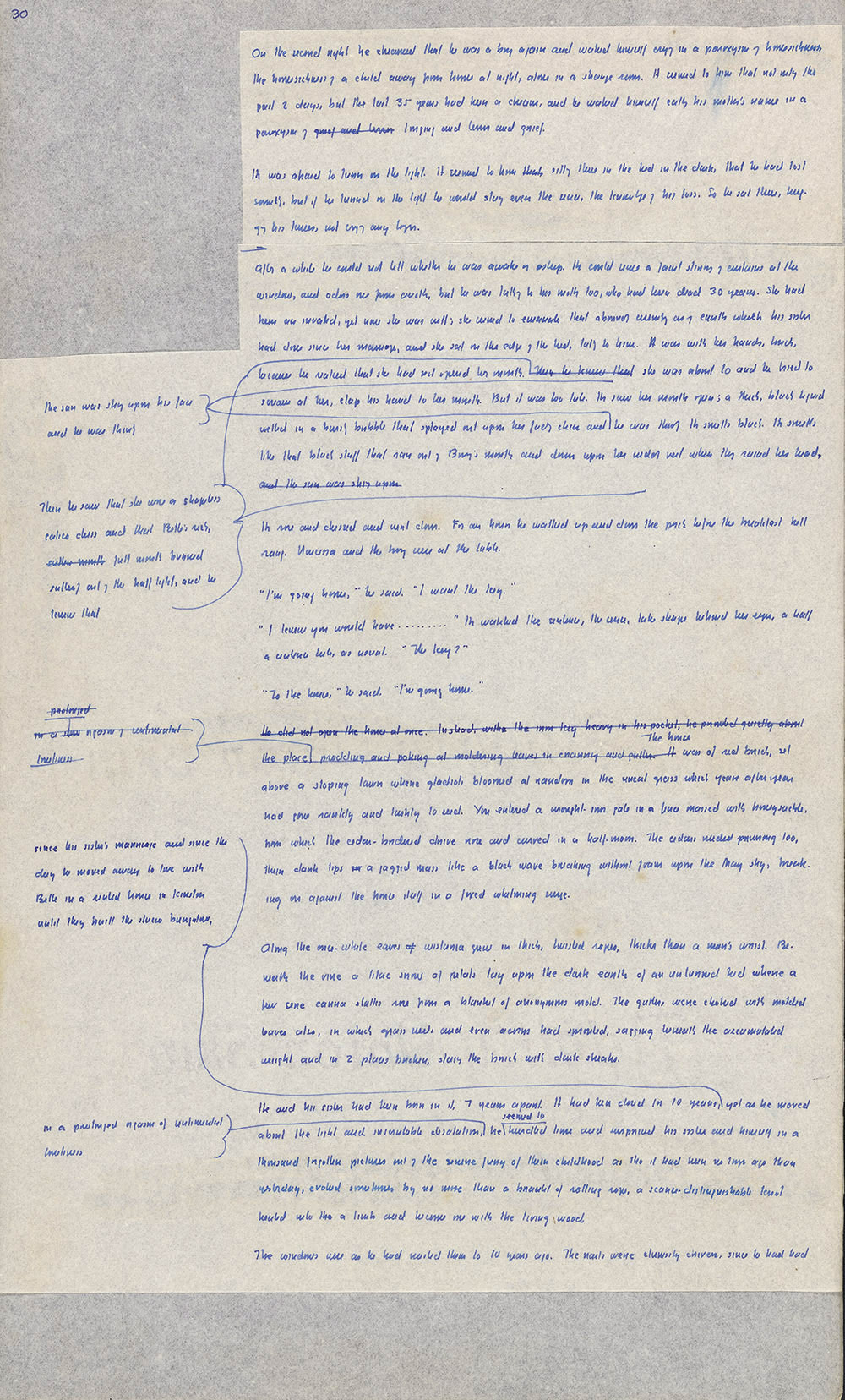

TRANSCRIPTION

On the second night he dreamed that he was a boy again and waked himself crying in a paroxysm of homesickness,

the homesickness of a child away from home at night, alone in a strange room. It seemed to him that not only the

past 2 days, but the last 35 years had been a dream, and he waked himself calling his mother's name in a

paroxysm of <grief and terror> longing and terror and grief.

He was about to turn on the light. It seemed to him <that>, sitting there in the bed in the dark, that he had lost

something, but if he turned on the light he would [illegible] even the sense, the knowledge of his loss. So he sat there, hug-

ging his knees, not crying any longer.

After a while he could not tell whether he was awake or asleep. He could sense a faint stirring of curtains at the

window, and odors [illegible], but he was talking to his mother too, who had been dead 30 years. She had

been an invalid, yet now she was well; she seemed to emanate that abounding serenity as of earth which his sister

had done since her marriage, and she sat on the edge of the bed, talking to him. It was with her hands, touch,

because he realized that she had not opened her mouth. <Then he knew that>

[margin: Then he saw that she wore a shapeless calico dress, and that Belle's rich, <sullen mouth> full mouth burned

sullenly out of the half light, and he knew that]

she was about to and he tried to

scream at her, clap his hand to her mouth. But it was too late. He saw her mouth open; a thick, black liquid

welled in a bursting bubble that splayed out upon her fading chin and

[margin: the sun was shining upon his face he was was thinking]

he was thinking He smells black. He smells

like that black stuff that ran out of Bovary's mouth and down upon her wedding vest when they raised her head,

<and the sun was shining upon>

He rose and dressed and went down. For an hour he walked up and down the park before the breakfast bell

rang. Narcissa and the boy were at the table.

"I'm going home," he said. "I want the key."

"I knew you would have . . . . . . . . . " He watched the sentence, the sense, take shape behind her eyes, a half

a sentence late, as usual. "The key?"

"To the house," he said. "I'm going home."

<He did not open the house at once. Instead, with the iron key heavy in his pocket, he prowled quietly about

the place>

[margin: <in a <<slow>> prolonged orgasm of sentimental loneliness>]

<prodding and poking at moldering leaves in cranny and gutter. He> The house was of red brick, set

above a sloping lawn where gladioli bloomed at random in the uncut grass which year after year

had gone rankly and lustily to seed. You entered a wrought-iron gate in a fence massed with honeysuckle,

from which the cedar-bordered drive rose and curved in a half-moon. The cedars needed pruning too,

their dark lips <in> a jagged mass like a black wave breaking without foam upon the May sky, break-

ing on against the house itself in a fixed whelming surge.

Along the once-white eaves <of> wisteria grew in thick, twisted ropes, thicker than a man's wrist. Be-

neath the vine a lilac snow of petals lay upon the dark earth of an unturned bed where a

few sere canna stalks rose from a blanket of anonymous mold. The gutters were choked with molded

leaves also, in which grass seeds and even acorns had sprouted, sagging beneath the accumulated

weight and in 2 places broken, staining the bricks with dark streaks.

He and his sister had been born in it, 7 years apart. It had been closed for 10 years,

[margin: since his sister's marriage and since the day he moved away to live with Belle in a rented house in Kinston

until they built the stucco bungalow,]

yet as he moved

about the tight and inscrutable desolation,

[margin: in a prolonged orgasm of sentimental loneliness]

he seemed to hurdled time and surprised his sister and himself in a

thousand forgotten pictures out of the serene fury of their childhood as though it had been no longer ago than

yesterday, evoked sometimes by no more than a bracelet of rotting rope, a scarce-distinguishable knot

healed into <the> a limb and become one with the living wood.

The windows were as he had nailed them to 10 years ago. The nails were clumsily driven, since he had had

|