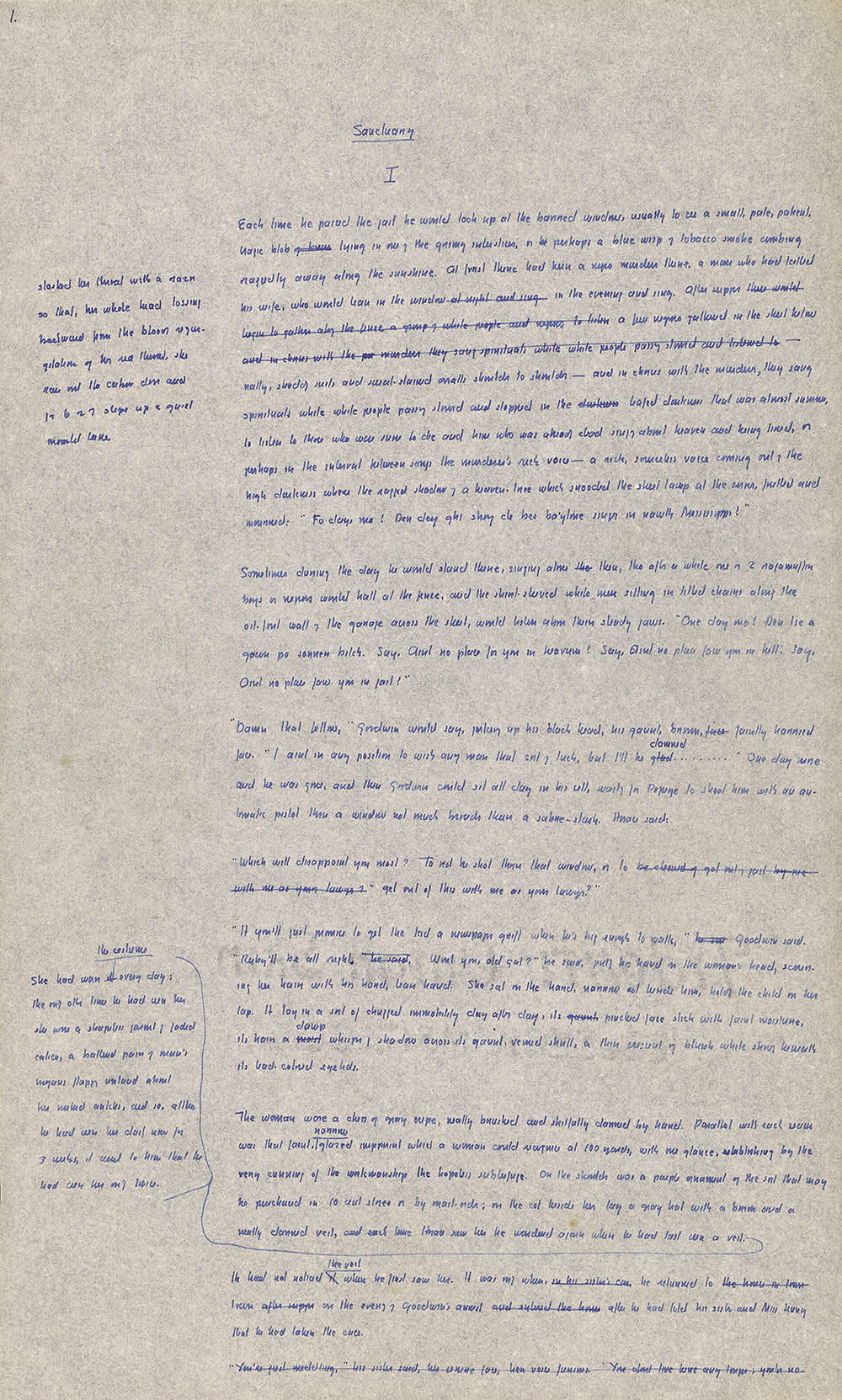

TRANSCRIPTION

Sanctuary

I

Each time he passed the jail he would look up at the barred window, usually to see a small, pale, patient,

tragic blob <of knuc> lying in one of the grimy interstices, or <[be?]> perhaps a blue wisp of tobacco smoke combing

raggedly away along the sunshine. At first there had been a negro murderer there, a man who had killed

his wife,

[margin: slashed her throat with a razor so that, her whole head tossing backward from the bloody regur-

gitation of her red throat, she ran out the cabin door and for 6 or 7 steps up a quiet moonlit lane]

who would lean in the window <at night and sing> in the evening and sing. After supper <there would

begin to gather along the fence a group of white people and negroes to listen> a few negroes gathered in the street below

<and in chorus with the murderer they sang spirituals while white people passing stood and listening to> –

natty, shoddy suits and sweat-stained overalls shoulder to shoulder – and in chorus with the murderer, they sang

spirituals while white people passing stood and stopped in the <darkness> leafed darkness that was almost summer,

to listen to those who were sure to die and him who was already dead singing about heaven and being tired, or

perhaps in the interval between songs the murderer's rich voice – a rich, sourceless voice coming out of the

high darkness where the ragged shadow of a heaven-tree which snooded the street lamp at the corner, fretted and

mourned: "Fo days do! Den dey ghy stroy de bes ba'ytone singer in nawth Mississippi!"

Sometimes during the day he would stand there, singing alone <[the?]> then, though after a while one or 2 ragamuffin

boys or negroes would halt at the fence, and the shirt-sleeved white men sitting in titled chairs along the

oil-foul wall of the garage across the street, would listen above their steady jaws. "One day mo! Den Ise a

gawn po sonnen bitch. Say, Aint no place for you in heaven! Say, Aint no place faw you in hell! Say,

Aint no place faw you in jail!"

"Damn that fellow," Goodwin would say, jerking up his black head, his gaunt, brown, <face> faintly harried

face. "I aint in any position to wish any man that sort of luck, but I'll be <glad> damned .........." One day more

and he was gone, and then Goodwin could sit all day in his cell, waiting for Popeye to shoot him with an au-

matic pistol through a window not much broader than a sabre-slash. Horace said:

"Which will disappoint you most? To not be shot through that window, or to <be cleared of [illegible] only just by me

with me as your lawyer?"> get out of this with me as your lawyer?"

"If you'll just promise to get the lad a newspaper grift when he's big enough to walk," <he sai> Goodwin said.

"Ruby will be all right. <" he said.> Wont you, old gal?" he said, putting his hand on the woman's head, scour-

ing her hair with his hard, lean hand. She sat on the hard, narrow cot beside him, holding the child on her

lap. It lay in a sort of drugged immobility day after day; its <gaunt,> pinched face slick with faint moisture,

its hair a <moist> damp whisper of shadow across its gaunt, veined skull, a thin crescent of bluish white showing beneath

its lead-colored eyelids.

The woman wore a dress of gray crepe, neatly brushed and skilfully darned by hand. Parallel with each seam

was that faint, narrow, glazed imprint which a woman could recognize at 100 yards, with one glance, establishing by the

very cunning of the worksmanship the hopeless subterfuge. On the shoulder was a purple ornament of the sort that may

be purchased in 10 cent stores or by mail-order; on the cot beside her lay a gray hat with a brim and a

neatly darned veil, and each time Horace saw her he wondered again when he had last seen a veil.

[margin: She had worn <it> the costume every day; the only other time he had seen her

she wore a shapeless garment of faded calico, a battered pair of man's brogans flapping unlaced about

her naked ankles, and so, although he had seen her daily now for 3 weeks, it seemed to him that he had

seen her only twice.]

He had not noticed <it> the veil when he first saw her. It was only when, <in his sister's car,> he returned to <the house in town>

town <after supper> on the evening of Goodwin's arrest <and entered the house> after he had told his sister and Miss Jenny

that he had taken the case.

<"You're just meddling," his sister said, her serene face, her voice furious. "You dont live here any longer; you've no->

|