TRANSCRIPTION

<VI>

<V>

<VI>

<XII>

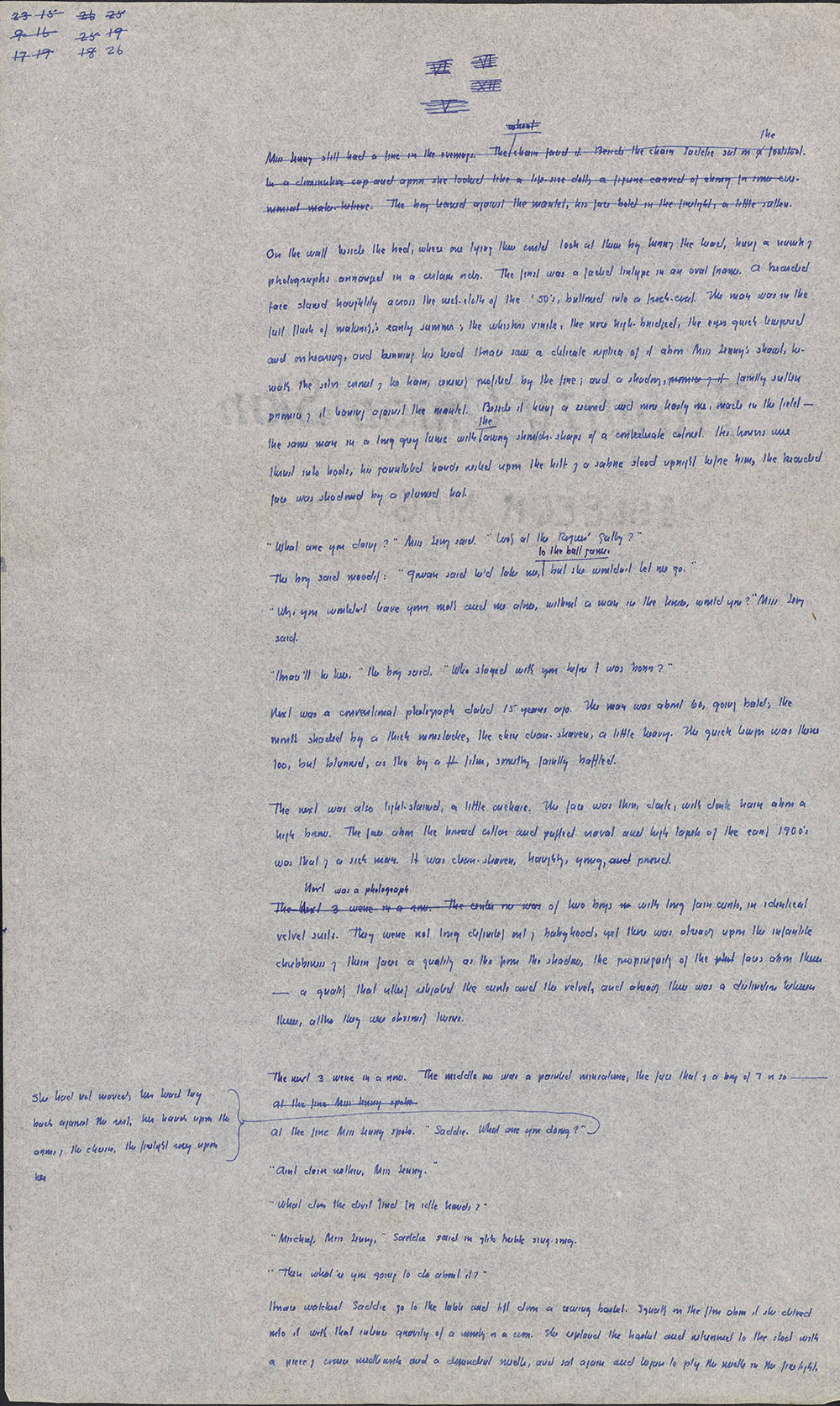

<Miss Jenny still had a fire in the evenings. The <<wheel>> chair faced it. Beside the chair Saddie sat on <<a>> the footstool.

In a diminutive cap and apron she looked like a life-size doll, a figure carved of ebony for some cere-

monial make-believe. The boy leaned against the mantel, his face bold in the firelight, a little sullen.>

On the wall beside the bed, where one lying there could look at them by turning the head, hung a number of

photographs arranged in a certain order. The first was a faded tintype in an oval frame. A bearded

face stared haughtily across the neck-cloth of the '50's, buttoned into a frock-coat. The man was in the

full flush of maturity's early summer; the whiskers virile, the nose high-bridged, the eyes quick-tempered

and overbearing, and turning his head Horace saw a delicate replica of it above Miss Jenny's shawl, be-

neath the silver coronet of her hair, serenely profiled by the fire; and a shadowy, <promise of it> faintly sullen

promise of it leaning against the mantel. Beside it hung a second and more hasty one, made in the field –

the same man in a long grey tunic with the awry shoulder-straps of a Confederate colonel. His trousers were

thrust into boots, his gauntleted hands rested upon the hilt of a sabre stood upright before him, the bearded

face was shadowed by a plumed hat.

"What are you doing?" Miss Jenny said. "Looking at the Rogues' Gallery?"

The boy said moodily: "Gowan said he'd take me, to the ball game, but she wouldn't let me go."

"Why, you wouldn't leave your mother and me alone, without a man in the house, would you?" Miss Jenny

said.

"Horace'll be here," the boy said. "Who stayed with you before I was born?"

Next was a conventional photograph dated 15 years ago. The man was about 60, going bald; the

mouth shaded by a thick moustache, the chin clean-shaven, a little heavy. The quick temper was there

too, but blurred, as though by a <fl> film, something faintly baffled.

The next was also light-stained, a little archaic. The face was thin, dark, with dark hair about a

high brow. The face above the broad collar and puffed cravat and high lapels of the early 1900's

was that of a sick man. It was clean-shaven, haughty, young, <and> proud.

<The next 3 were in a row. The center one was> Next was a photograph of two boys <in> with long fair curls, in identical

velvet suits. They were not long definitely out of babyhood, yet there was already upon the infantile

chubbiness of their faces a quality as though from the shadows, the propinquity of the <phot> faces above them

– a quality that utterly relegated the curls and the velvet, and already there was a distinction between

them, although they were obviously twins.

The next 3 were in a row. The middle one was a painted miniature, the face that of a boy of 7 or so –

<At the fire Miss Jenny spoke.>

At the fire Miss Jenny spoke. "Saddie. What are you doing?"

[margin: She had not moved; her head lay back against the rest, her hands upon the arms of the chair, the firelight rosy upon her]

"Aint doin nothin, Miss Jenny."

"What does the devil find for idle hands?"

"Mischief, Miss Jenny," Saddie said in glib treble sing-song.

"Then what're you going to do about it?"

Horace watched Saddie go to the table and lift down a sewing basket. Squatting on the floor above it she delved

into it with that intense gravity of a monkey or a coon. She replaced the basket and returned to the stool with

a piece of coarse needle work and a dependent needle, and sat again and began to ply the needle in the firelight.

|