|

CLOSE WINDOW |

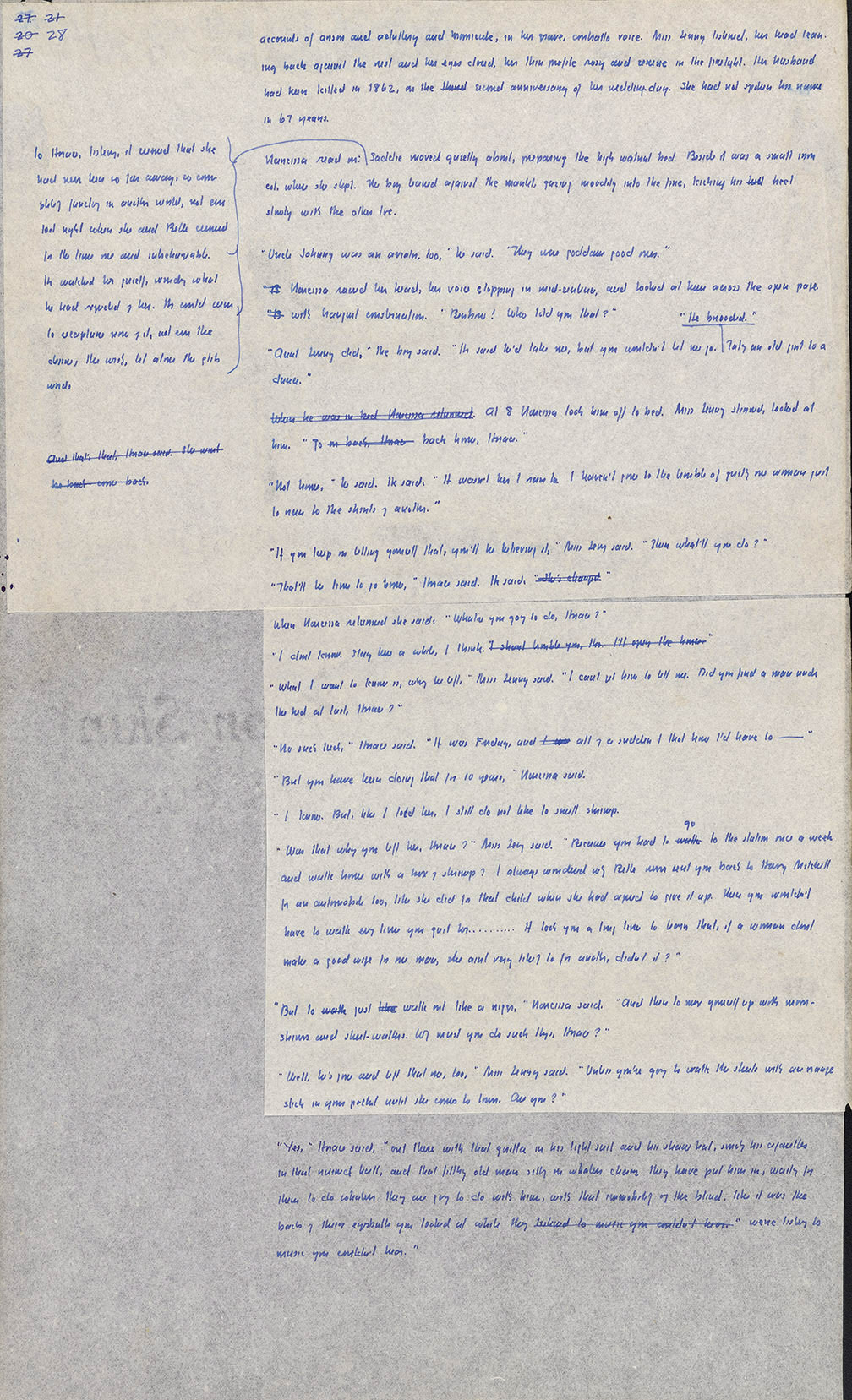

William Faulkner Foundation Collection, 1918-1959, Accession #6074 to 6074-d, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va. [Item Metadata: IA:6) SANCTUARY Autograph manuscript. 138 p. (137 R, 1 V) on 137 l. Slipcase. ] |

|

accounts of arson and adultery and homicide, in her grave, contralto voice. Miss Jenny listened, her head lean- Narcissa read on: "Uncle Johnny was an aviator, too," he said. "They were goddam good ones." <"B> Narcissa raised her head, her voice stopping in mid-sentence, and looked at him across the open page "Aunt Jenny did," the boy said. "He said he'd take me, but you wouldn't let me go. "He brooded." Taking an old girl to a <When he was in bed, Narcissa returned.> At 8 Narcissa took him off to bed. Miss Jenny stirred, looked at "Not home," he said. He said, "It wasn't her I ran to. I haven't gone to the trouble of quitting one woman just "If you keep on telling yourself that, you'll be believing it," Miss Jenny said. "Then what'll you do?" "That'll be time to go home," Horace said. He said, <"She's changed."> When Narcissa returned she said: "What're you going to do, Horace?" "I dont know. Stay here a while, I think. <I shant trouble you, though. I'll open the house."> "What I want to know is, why he left," Miss Jenny said. "I cant get him to tell me. Did you find a man under "No such luck," Horace said. "It was Friday, and <I w> all of a sudden I thought how I'd have to — " "But you have been doing that for 10 years," Narcissa said. "I know. But, like I told her, I still do not like to smell shrimp. "Was that why you left her, Horace?" Miss Jenny said. "Because you had to <walk> go to the statiion once a week "But to <walk> just <like> walk out like a nigger," Narcissa said. "And then to mix yourself up with moon- "Well, he's gone and left that one, too," Miss Jenny said. "Unless you're going to walk the streets with an orange "Yes," Horace said, "out there with that gorilla in his tight suit and his straw hat, smoking his cigarettes |