- About

- Search

- Events

- Characters

- Locations

- Visualizations

- Location-Character

- Character-Character

- Character-Event

- Heatmaps

- Photographs

- Narrative Analysis

- Commentaries

- Faulkner & Maps

- Cemeteries

- Genealogies

- Race & Place

- Absalom, Absalom!

- Teaching & Learning

- Indexes

DIGITAL Yoknapatawpha · First Families

About

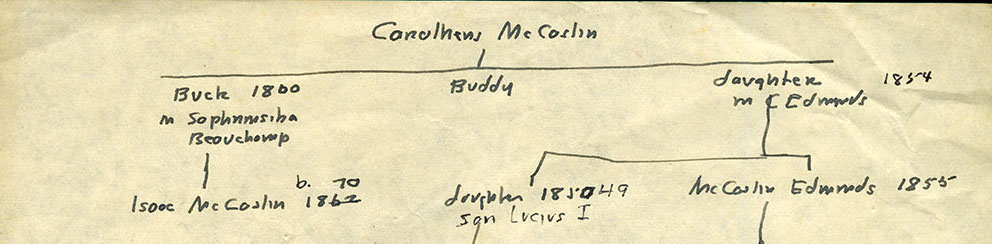

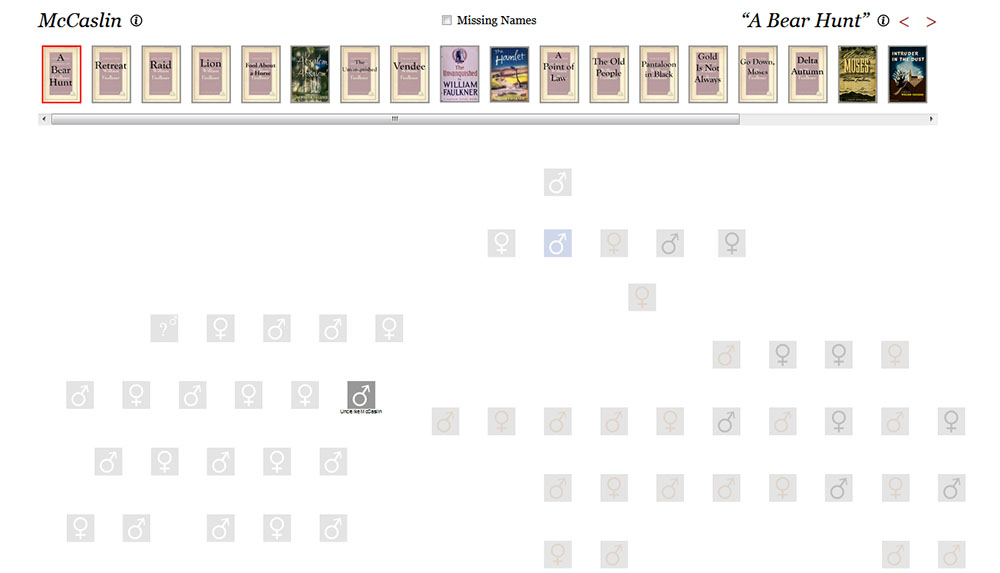

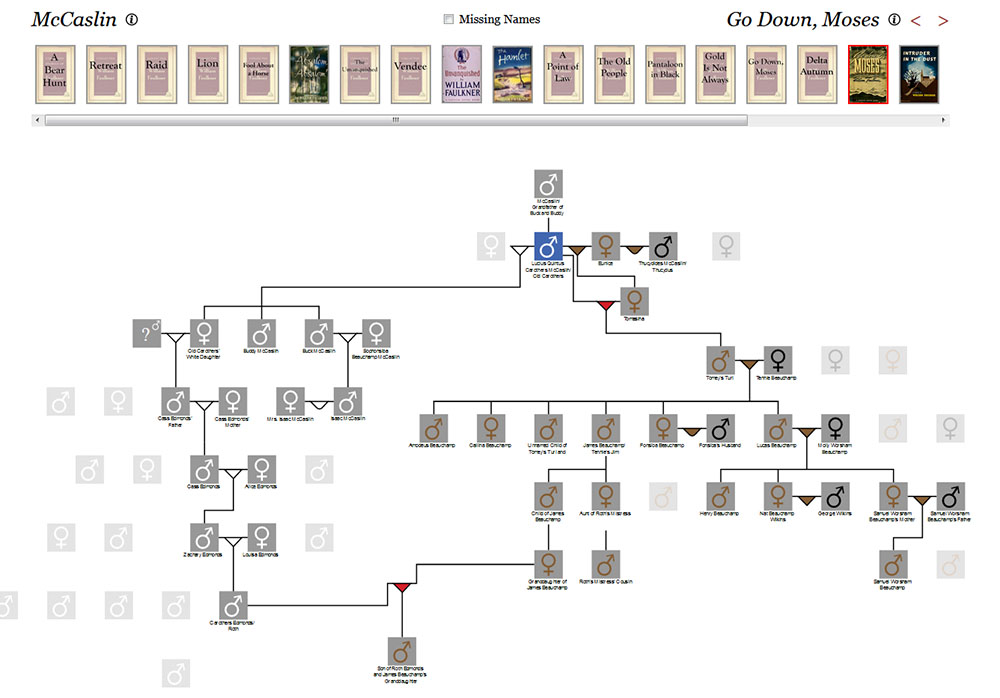

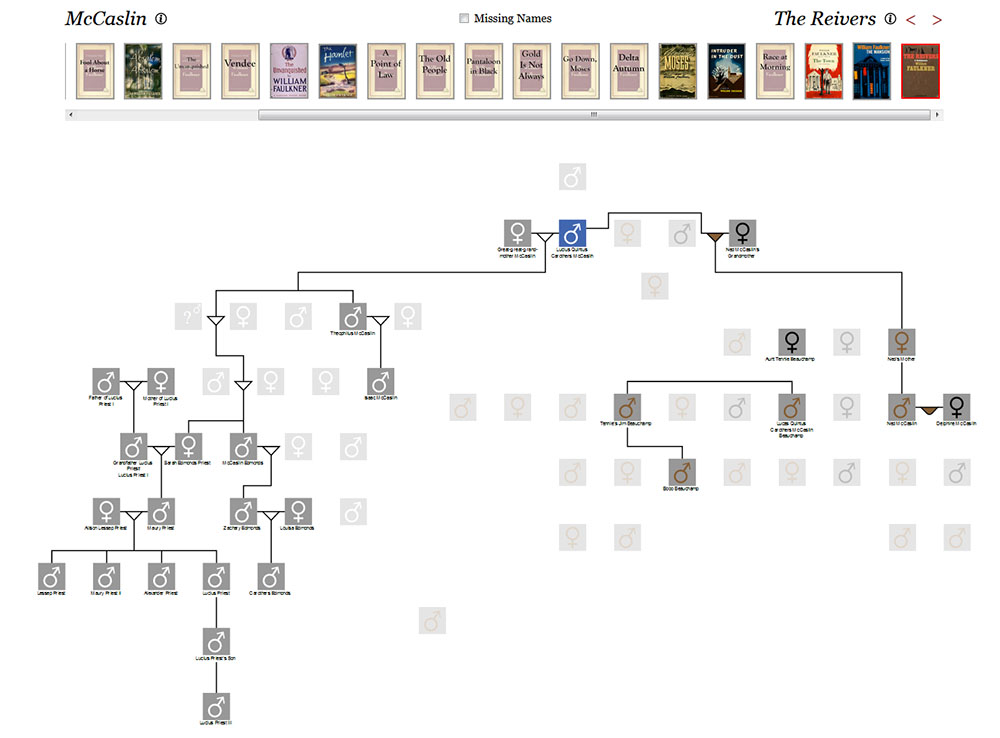

Detail from Faulkner's Charts of McCaslin Family. (To see whole page, click here.) About the GenealogiesFor help navigating the display, please watch the 7-minute Demo. Families are central to the world Faulkner creates in the Yoknapatawpha fictions - especially the families that recur in multiple texts, like the eleven you can explore through these genealogies. Faulkner makes sustained use of these families to develop several of his own recurring themes, from the way the past shapes and often determines the present to the way the social landscape of Yoknapatawpha sits atop the fault line of race. Quentin Compson, for example, struggles in vain to escape his childhood past as his parents' son and his sister's brother in The Sound and the Fury, and then in Absalom, Absalom! has to contend with the cultural legacy of slavery and racism as the story he inherits from his grandfather and father plays out through the generations fathers and sons in the Sutpen family. For all the thematic weight they carry, Faulkner's recurring families are conceived realistically. If, for instance, the repetition of names like "Bayard" on the Sartoris family tree or - perhaps most notoriously - "Quentin" him- and herself among the Compsons is a symbolically effective way to demonstrate how the past perpetuates itself into the future, such repetitions are also an accurate representation of Southern cultural practice. This pattern extends even to calling the one Bayard Sartoris who never served in the military "Colonel Sartoris" as if it were a title he inherited from his father. But at the same time these repetitions can be very confusing for first-time readers - especially when coupled with Faulkner's own carelessness about intertextual consistency, so that "Lucas Beauchamp" in a cluster of texts can abruptly become "Luke" in a new one. For these and other reasons it's easy to understand why Faulkner critics and scholars have created so many genealogical charts. As we created the genealogies here we regularly and gratefully consulted this previous work. But working in a digital medium allows us to re-present Faulkner's families dynamically, in a way that is closer to the imaginative and moral ferment in which Faulkner created and re-created them over the course of his career. In some cases he had a family's history largely in focus from the start. All but four of the fourteen people on the MacCallum family tree, for example, already appear in Flags in the Dust. Even the larger Sartoris family is well-defined in that first Yoknapatawpha fiction: by the end of Flags twenty of the thirty people who will ultimately be identified as 'Sartorises' are in place. But he re-imagines the contours of this genealogy very dramatically in "There Was a Queen," the seventh of his texts to include at least one 'Sartoris,' when the narrator acknowledges that Elnora Strother and her children are all among the descendants of Colonel Sartoris (the one who did serve in the Confederate Army), though the people on this biracial and illegitimate branch of the family tree live as servants in a cabin behind the mansion where the publicly acknowledged white members of the family live and die. "There Was a Queen" was published in 1933, just four years after Flags. On the one hand, Faulkner's decision to reconstruct this family of plantation aristocrats to acknowledge the way sex and kinship often transgress the color line that is so deeply entrenched in theory in the Jim Crow culture of Faulkner's South anticipates the powerful way his writing over the coming years will use "family" as the site for looking hard at Southern history: see Absalom, Absalom! and especially Go Down, Moses. On the other, after "There Was a Queen" Faulkner will go on to write nineteen more texts in which at least one 'Sartoris' appears or is mentioned - and none of them make any reference to the non-white members of the family as members of the family. A static chart of the Sartorises can include both sides of the family; Edward Volpe's chart of the "Sartoris Genealogy" in A Reader's Guide to William Faulkner does, while Cleanth Brooks' chart in William Faulkner: The Yoknapatawpha Country does not. But no static chart can show this pattern of admission and denial about the behavior of the plantation aristocracy, can define and re-define and then re-re-define the Sartoris family as the individual works do. Elnora, who also appears on two of the Strothers family trees, is and isn't a 'Sartoris.' Issetibbeha is Ikkemotubbe's son in "Red Leaves" and then his uncle a decade later in "The Old People" - which is why, by the way, our representation of the Indian family has two names. All these families grow and shrink in some ways. But as one other example of why it's important to study them dynamically, let's look at three of the twenty-two McCaslin family charts. By the end of Faulkner's career there are sixty-one members of the extended McCaslin family, which includes Edmondses, Beauchamps and Priests, making it the second largest after the Snopeses. But this family tree grows slowly. The first McCaslin to appear is 'Uncle Ike'; he's an old hunter and a minor character in "A Bear Hunt" (1934). Here's the chart for that text:  You can see by the faint icons above the other sixty characters whom Faulkner will eventually create, but in the first eight texts that include a member of the McCaslin family only two additional ones appear: Ike's grandson named Theophilus in one of the other two that include Ike, and 'Uncle Buck' (who is also named Theophilus once) in the other five, all but one in the series of Unvanquished stories Faulkner wrote in mid-1930s. When he revised those stories for publication in the novel The Unvanquished Faulkner begins to describe Buck's family: they are slave-owners with "a big bottom-land plantation" (46); Buck has a twin brother, Uncle Buddy or Amodeus, and a deceased, unnamed father. Ike is not mentioned. On the other hand, "Isaac McCaslin, 'Uncle Ike'" are the first words of Go Down, Moses (1942), and the McCaslin family that appears in that novel is strikingly re-configured, not only much bigger but now as black and biracial as it is white:  There's a textually complex story behind the process that led Faulkner to this representation of the family; you can explore it further by way of the collected McCaslin charts here or in the other sections of this project that focus on Go Down, Moses. Here it's enough to note that in Moses that unnamed father who had barely been mentioned in The Unvanquished and his grandson, the Ike McCaslin who played very minor roles in three stories, move to the center of a major novel that also moves the McCaslin family to the same central place in the saga of Yoknapatawpha as the Sartorises, the Compsons or - to cite the family that has the most in common with them as a re-presentation of the plantation aristocracy and the past it created - the Sutpens. Sutpen's family, however, largely disappears after Absalom! The McCaslins not only recur in five more texts; in Faulkner's very last novel, The Reivers in 1962, the family is again at the center of the narrative - though again, it's been radically configured:  There are over a dozen new names on this family tree, including five new biracial descendants of the original father. In addition, there is an entirely new branch: the Priests. Again, the implications of this revision are too complex for this mini-essay devoted to trying to explain why we wanted to use the technology to provide a new way to see Faulkner's recurring families, but one purely mathematical point is that in Go Down, Moses the McCaslin family (like Yoknapatawpha itself, according to Faulkner's 1936 map of the county) has more non-white members than white ones - 24 to 15. With the addition of these Priests, however, the totals for The Reivers are eight non-white and twenty-four white, and for the family's aggregate chart, 31 white to 30 non-white. How this one family evolves over thirty years can perhaps help us appreciate the larger story of Faulkner's career as a writer, a historian, a moralist, a Southerner. Citing this resource: |

Demo

Legend

Legend

Characters

| The male and female icons for family members identified as white. |

| The male and female icons for family members identified as Negro. |

| The male and female icons for family members identified as Indian. |

| We use these icons for all the characters who are identified as racially mixed, regardless of the races and generational history involved - i.e. for a character with one white and one Negro parent, or a character with three white and one Indian grandparents, etc. |

| The blue box identifies this character as the first member of of the family to arrive in Yoknapatawpha; in some cases that "first arrival" changes from text to text. (There's no way to identify the equivalent "first arrival" among Faulkner's Indians, and it seems inappropriate to identify any one in a Negro family this way, given that they were brought to Yoknapatawpha as slaves. |

| This pair of icons represents the way we display a mother or a father whom we know must have been there, biologically, but about whom a text says absolutely nothing. |

| These "faded" icons appear on the genealogical charts for specific texts to indicate the members of a family who are not present or mentioned in that text. |

Relationships

| A marriage between two characters of the same race who have offspring. |

| A childless marriage between two characters of the same race. |

| An interracial relationship with children. |

| An interracial relationship without children. |

| An extramarital relationship with (illegitimate) children. |

| A bigamous marriage with children. |

| An incestuous relationship that results in a child. |

| We use this sign to indicate that there is no information, in this particular text, to enable readers to determine which of the parents belongs to the family being displayed. |

| This indicates that the same character is (in some texts) the child and (in others) the grandchild of another character. It only appears in (some of) the Aggregate charts. |

| This appears only once, on the genealogical chart for the Chickasaw family. It is our solution to the problem Faulkner created when he made a single character descend from both the male and female lines in Issetibbeha's family. |

Names

| From text to text, Faulkner often refers to the same character under different names. On the Aggregate charts we list all the names a character has across all the texts in which she or he appears (top left: Colonel John Sartoris' sister); in the chart for a specific text, we use the name worn by that character in that work (bottom left: Virginia Du Pre in the novel Sanctuary, where she is never identified by any other name than "Miss Jenny"). From any single text genealogy you can toggle All Names to confirm, for example, that "Miss Jenny" is "Virginia Du Pre." |