Absalom, Absalom! : Chapter-by-Chapter Chronology

- Grandfather-Quentin

- Narrator

- Sutpen

- Shreve

- Father

- Quentin

- Father-Grandfather

- Midwife

- Major de Spain

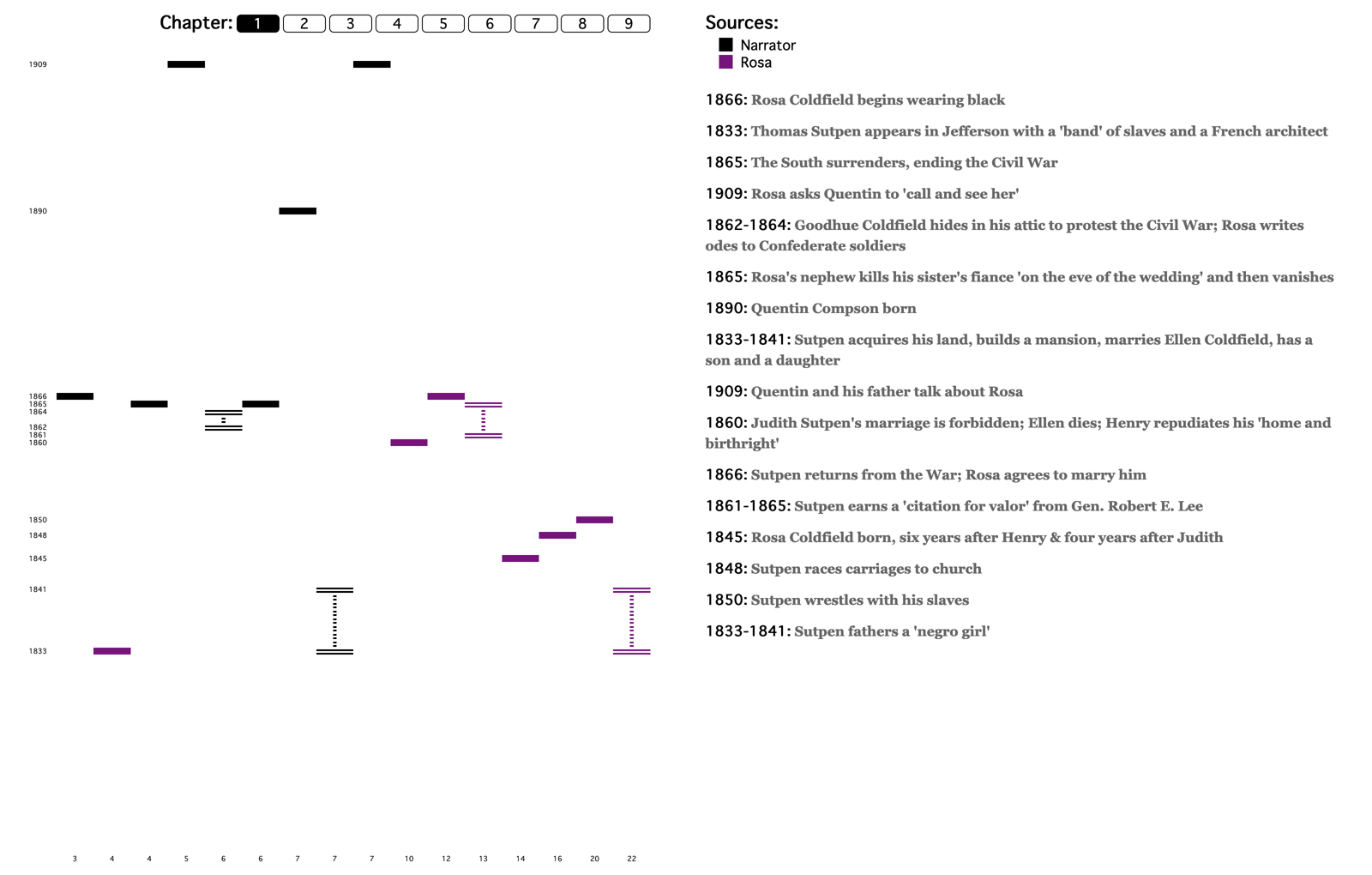

About Absalom, Absalom!: Chapter-by-Chapter ChronologyThe first section below explains why, given the fact that most editions of Absalom include a “Chronology” of significant events written by Faulkner himself, we designed this digital chronology for first-time readers. The second section, A Pair of Warnings, explains how both “significant” and “events” are conditional terms, not definitive claims. The third section describes how to use use our chronology. Rationale: The idea for this presentation grew from my experience teaching Absalom to college students who were motivated and experienced with other Faulkner texts but who, because of the novel’s extremely difficult prose style, found themselves reaching the end of a chapter or even the bottom of a page with no clear idea what is happening in the story. The novel’s very first reader was Faulkner’s editor, Hal Smith. As he worked through the manuscript Smith grew increasingly alarmed about this problem. Probably at his request, Faulkner created a map of Yoknapatawpha, a “Genealogy” of the major characters, and a “Chronology” listing 33 important events in the story that lies behind the novel’s narrative. Random House printed these explanatory materials at the end of the book, and they are still included in the Vintage International edition that my students were reading. I was reluctant, however, to point them to Faulkner’s Chronology for help keeping track of the plot of the story. Absalom unfolds with deliberate ambiguity and uncertainty through the accounts of five different story-tellers – a third-person narrator, Miss Rosa, Mr. Compson, Quentin and Shreve – who use a dozen more sources along with their own imaginations and personal prejudices to try to reconstruct the past that haunts the South. Their versions complement, complicate and contradict each other as the novel works toward what may be a dramatic epiphany about the past and its legacy at the end of the penultimate chapter. Consulting Faulkner’s Chronology before you’ve read the whole narrative, however, is like reading an inept detective fiction that identifies who done it less than halfway through the book: five of the Chronology’s first six items give away crucial plot points that the actual narrative withholds until it approaches the end. To give students an alternative way to get a grasp on the main events of the story, one that stays closer to the actual experience of reading the novel as that story is told and retold, Will Rourk and I in 2011 created a Flash-based, online prototype of this chapter-by-chapter chronology. Read each chapter first, I told my students, and then use the electronic chronology to clarify the main events disclosed in that chapter. That Flash-based version no longer works. This version of the chronology has been rebuilt by Doug Ross. And while it was designed with first-time readers in mind, I hope it might help even veteran ones discover new ways to engage the text. It certainly did that for me. Until I saw the graphs of the nine chapters, for instance, I hadn’t realized just how many significant events I had selected cluster around 1860-1866 – the era of the Civil War. While Faulkner’s story takes place across more than a century, 53 of the 126 events in this chronology (42%) occur within that six-year period. Sure, among its main cast members are a Confederate general, a colonel, a major, a lieutenant and a private – but the Union army is never seen, and there are almost no Northern characters at all. The story does intersect briefly, for example, with the Battle of Gettysburg. But it is by no means a “war story.” That epiphany at the end of Chapter 8 I mentioned is by far the book’s longest scene with a military setting, but the conflict it dramatizes, while unmistakably Southern, is not at all military, and its major characters are all wearing Confederate uniforms. Graphing the narrative helped me realize how powerfully, and how tragically, Absalom, Absalom! redefines the familiar phrase “brother against brother.” A Pair of Warnings. First caveat: this chronology consists of 126 events, between 8 and 16 per chapter. It includes almost all of the 33 in Faulkner’s Chronology, but adds many others that were chosen by me for their narrative and thematic significance. Another editor could have selected more, or fewer, or different events. I don’t claim my list is definitive, but rather – like each story-teller’s version of the story – an interpretive act. My self-imposed limit of 16 events per chapter is meant to keep each batch small enough to be manageable and useful to a first-time reader. A second caveat: with this novel the word event should always be in quotation marks. There is no “event” on these lists, or Faulkner’s for that matter, that we can say “really happened.” One of novel’s central themes is how the past can only be reconstructed, not lived firsthand, and so even the reliability of the book’s third-person narrator, who is looking back on the story a quarter century after its last event takes place, may be unreliable. It is up to each reader to decide which story-tellers, sources or events give us the best access to the past. For this reason, our chronology color-codes the specific narrator or narrative source for each event. Black icons are used, for example, to identify the third-person narrator’s contributions. Between 2 and 10 sources are responsible for the reconstructions in each chapter; they are identified at the top of each chapter’s page. Here are all 16 sources and their respective color codes:  (NOTE: hyphens and stripes are used when it seems a source is relying on and perhaps revising another source, such as when Mr. Compson in 1909 relays what his father, General Compson, told him years earlier. The composites “Quentin-Shreve” and “Shreve-Quentin” are our way of distinguishing which is actually speaking in those passages where the narrative says the two are in perfect agreement; the actual speaker is listed first.) Using the Chronology: Your first step in using the program is choosing the chapter you want to review by clicking on any of the 9 boxes at the top left of the page. Your choice will be highlighted in red, as Chapter 1 is here. All the following illustrations are from that chapter. Below you can see how that chapter’s 16 events are displayed on both the lefthand graph and the righthand list.  The list of Chapter 1 events on the righthand is sorted in the order of their appearance in the text, from page 3 to page 22 in the 2011 Vintage paperback. On the graph, the same events are located in both narrative and chronological order. The horizontal x-axis plots events from left to right as they occur in the text; the numbers below the axis are page numbers. The vertical y-axis indicates when an event occurs in time, from 1800 at the bottom up to 1910 at the top; the numbers to the left of the y-axis are dates. (NOTE: when you use the program on your computer or laptop, you may have to scroll down to see the earliest events on the graph or the events that occur later in a chapter on the righthand list.)

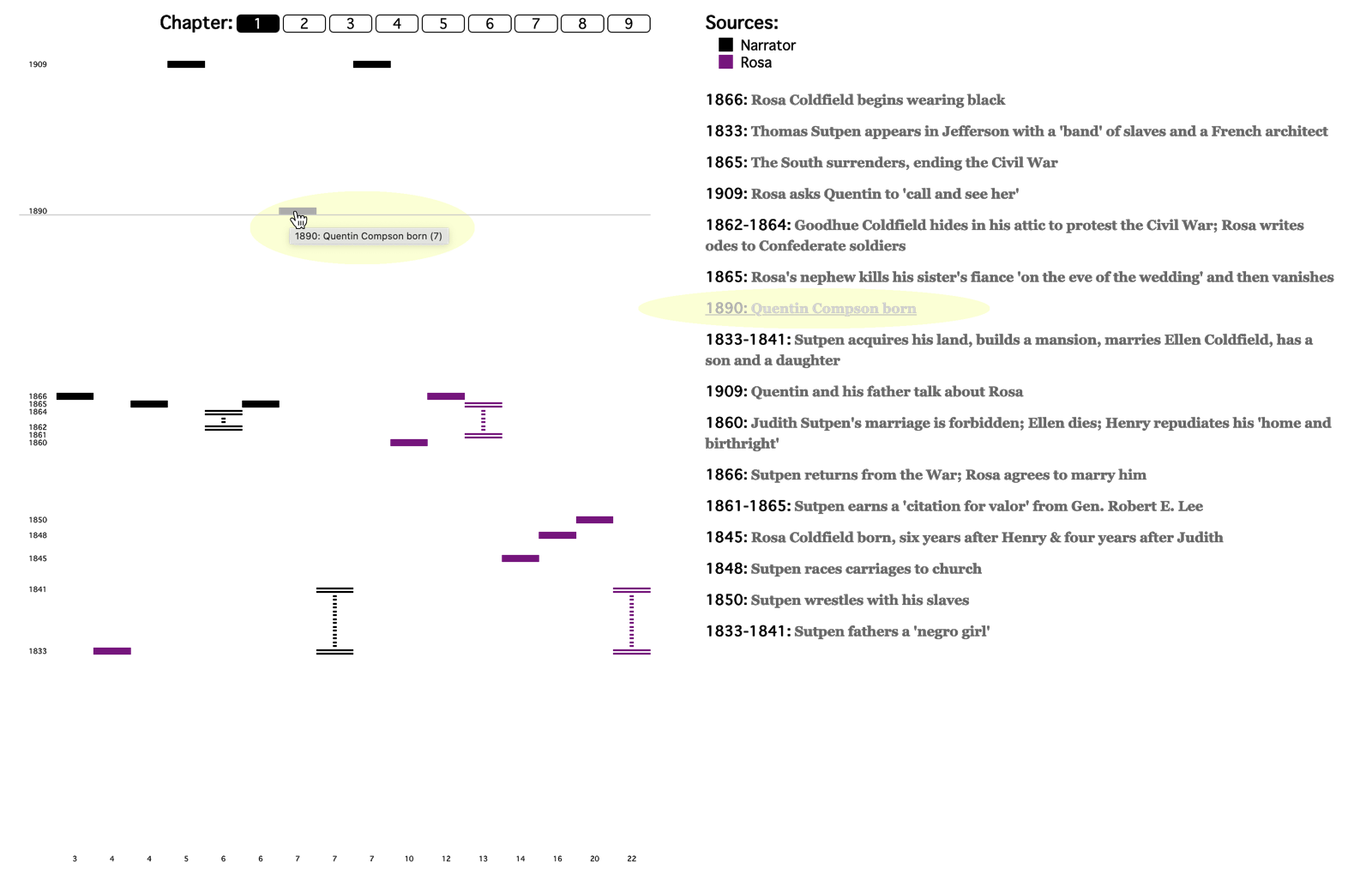

The icon in the example highlighted here is black, identifying the novel’s narrator as its source. It appears at the left of the x-axis and near the top of the y-axis – that is, early in the narrative but late in the story. The example also highlights what happens when you move your cursor over an icon: a brief description of the event itself as well as its date and page number pop up on the graph. The graph’s visualization of this information may prompt us to reflect on one of the central facts of this novel: that Quentin is present from the beginning of the narrative to its final page, yet is born only after almost all the story is in the past that Faulkner finds many ways to remind us “is never dead.” You can also see in this example how the graph and the list are interlinked: with your cursor over the icon, the position of the event on the list is indicated. Highlighted on the illustration below is the icon we use to plot multi-year events on the graph:

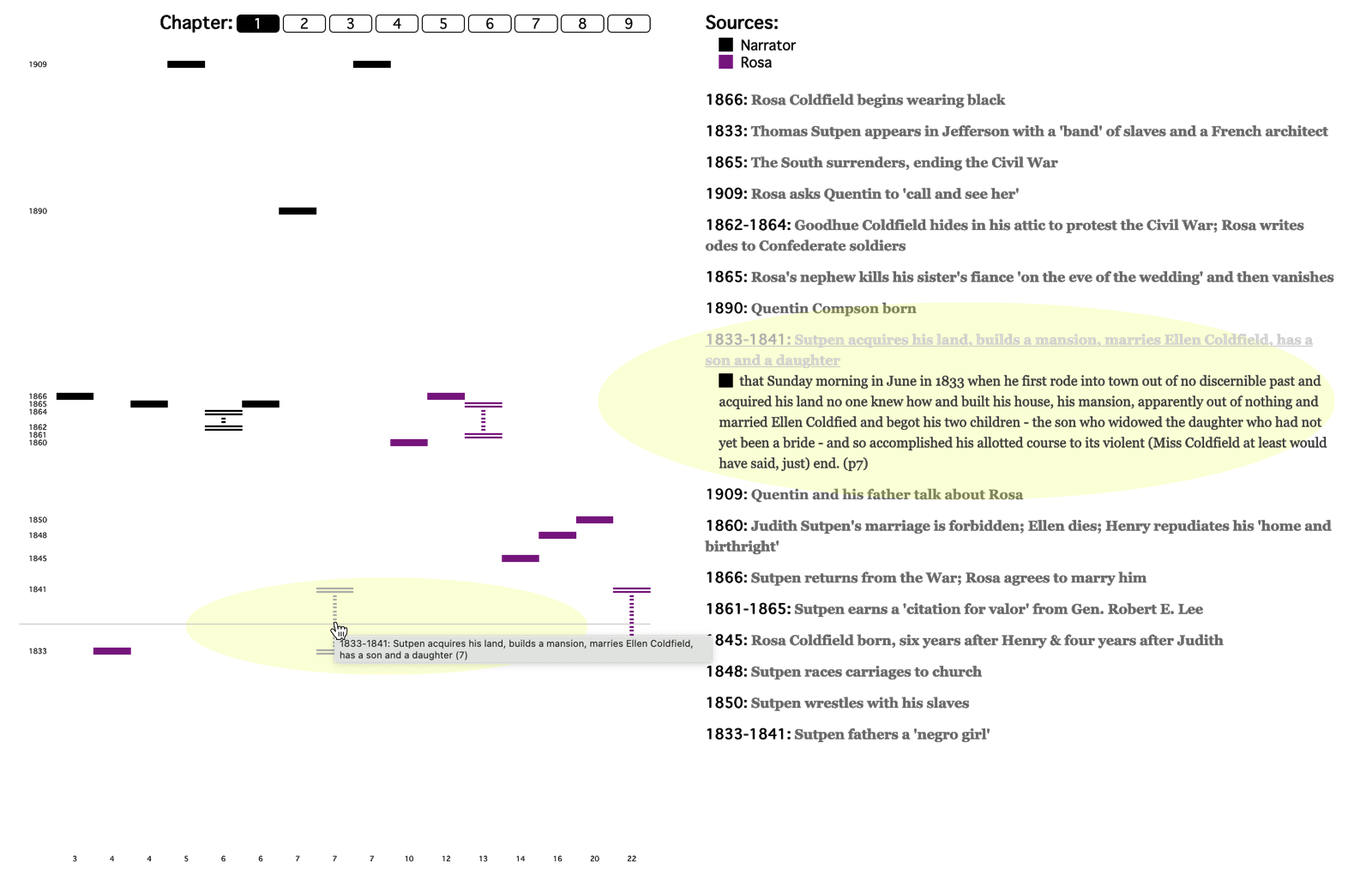

I wrote the descriptions of the events on graphs and list, but this illustration also shows what happens when you click on an graph icon or a list item: clicking expands the list entry to include the passage from Absalom where the event is first mentioned. This feature allows you to work back from our re-presentation of the novel to Faulkner’s actual text. That, of course, is what we hope this resource ultimately gives you: a means, not an end – a way to return to Absalom, Absalom! perhaps a bit readier to appreciate and understand it. – Stephen Railton For more on Faulkner, Hal Smith, and the published “Chronology,” see “Absalom, Absalom! Manuscripts Etc. and Absalom, Absalom! The Chronologies - but remember that Faulkner’s chronology includes a lot of spoilers! For more on the novel’s various sources, see The Narrative Sources of Absalom, Absalom! Citing this resource:

|

"He told Grandfather about it," he said. "That time when the architect escaped, tried to, tried to escape into the river bottom and go back to New Orleans or wherever it was," (p177)

Because he was born in West Virginia, in the mountains where - " ("Not in West Virginia," Shreve said. "Because if he was twenty-five years old in Mississippi in 1833, he was born in 1808. And there wasn't any West Virginia in 1808 because - " "All right," Quentin said. " - West Virginia wasn't admitted - " "All right all right" Quentin said. " - into the United States until - " "All right all right all right," Quentin said.) " - where what few other people he knew lived in log cabins boiling with children like the one he was born in - " (p179)

When he was a child he didn't listen to the vague and cloudy tales of Tidewater splendor that penetrated even his mountains because then he could not understand what the people meant . . . So he had hardly heard of such a world until he fell into it. . . . They fell into it, the whole family, returned to the coast from which the first Sutpen had come (when the ship from the Old Bailey reached Jamestown probably), tumbled head over heels back to Tidewater by sheer altitude, elevation and gravity . . . across the Virginia plateau and into the slack lowlands about the mouth of the James River. . . . (he was ten then) (pp180-81)

He didn't even know he was innocent that day when his father sent him to the big house with the message. He didn't remember (or did not say) what the message was, apparently he still didn't know exactly just what his father did, what work (or maybe supposed to do) the old man had in relation to the plantation - a boy either thirteen or fourteen, he didn't know which, in garments his father had got from the plantation commissary and had worn out and which one of the sisters had patched and cut down to fit him and he no more conscious of his appearance in them or of the possibility that anyone else would be than he was of his skin, following the road and turning into the gate and following the drive up past where still more niggers with nothing to do all day but plant flowers and trim grass were working, and so to the house, the portico, the front door, thinking how at last he was going to see insider of it, . . . he told Grandfather how, before the monkey nigger who came to the door had finished saying what he did, (pp185-86) And now he stood there before that white door with the monkey-nigger barring it and looking down on him in his patched made-over jeans clothes and no shoes . . . and he never even remembered what the nigger said, now it was the nigger told him, even before he had had time to say what he came for, never to come to that front door again but to go around to the back. (p188) Because he was not mad. He insisted on that to Grandfather. He was just thinking, because he knew that something would have to be done about it; he would have to do something about it in order to live with himself for the rest of his life (p189) [he] looked out from whatever invisible place he (the man) happened to be at the moment, at the boy outside the barred door in his patched garments and splayed bare feet, looking through and beyond the boy, he himself seeing his own father and sisters and brothers as the owner, the rich man (not the nigger) must have been seeing them all the time - as cattle, creatures heavy and without grace, brutely evacuated into a world without hope or purpose for them, . . . with for sole heritage that expression on a balloon face bursting with laughter which had looked out at some unremembered and nameless progenitor who had knocked as a door when he was a little boy and had been told by a nigger to go around to the back. (p190) I went up to that door for that nigger to tell me never to come to that front door again and I not only wasn't doing any good to him by telling it or any harm to him by not telling it, there aint any good or harm either in the living world that I can do to him. It was like that, he said, like an explosion - a bright glare that vanished and left nothing, no ashes nor refuse: just a limitless flat plain with the severe shape of his intact innocence rising from it like a monument. . . . 'So to combat them you have got to have what they have that made them do what he did. You got to have land and niggers and a fine house to combat them with. You see?' and he said Yes again. He left that night. He waked before day and departed just like he went to bed: by rising from the pallet and tiptoeing out of the house. He never saw any of his family again. He went to the West Indies. (p192)

saying it just like that day thirty years later when he sat in Grandfather's office (in his fine clothes now, even though they were a little soiled and worn with three years of war . . .)" (p193) and Sutpen came home in '64 with the two tombstones and talked to Grandfather in the office that day before both of them went back to the war; (p217)

just told Grandfather how he had put his first wife aside like eleventh and twelfth century kings did: 'I found that she was not and could never be, through no fault of her own, adjunctive or incremental to the design which I had in mind, so I provided for her and put her aside.' (p194) when he repudiated that first wife and that child when he discovered that they would not be adjunctive to the forwarding of the design. . . . the marriage settlement which he had entered in good faith, with no reservations as to his obscure origin and material equipment, while there had been not only reservation but actual misrepresentation on their part and misrepresentation of such a crass nature as to have not only voided and frustrated without his knowing it the central motivation of his entire design, but would have made an ironic delusion of all that he had suffered and endured in the past and all that he could ever accomplish in the future toward that design - . . . Yes, sitting there in Grandfather's office trying to explain . . . 'they deliberately withheld from me the one fact which I have reason to know they were aware would have caused me to decline the entire matter, otherwise they would not have withheld it from me - a fact which I did not learn until after my son was born.' (pp211-12)

He was telling some more of it, already into what he was telling yet still without telling how he got to where he was nor even how what he was no involved in (obviously at least twenty years old now, crouching behind a window in the dark and firing the muskets through it which someone else loaded and handed to him) . . . he not telling how he got there, what had happened during the six years between that day when he, a boy of fourteen who knew no tongue but English and not much of that, had decided to go to the West Indies and become rich, and this night when, overseer or foreman or something to a French sugar planter, he was barricade in the house with the planter's family (and now Grandfather said there was the first mention - a shadow that almost emerged for a moment and then faded again but not completely away - of the - - " ("It's a girl," Shreve said. "Dont tell me. Just go on.") "whom he was to tell Grandfather thirty years afterward he had found unsuitable to his purpose and so put aside, though providing for her) and a few frightened half-breed servants which he would have to turn from the window from time to time and kick and curse into helping the girl load the muskets which he and the planter fired through the windows, . . . while the two servants and the girl whose christian name he did not yet know loaded the muskets which he and the father fired at no enemy but at the Haitian night itself, (pp198-99) and how on the eighth night the water gave out and something had to be done and so he put the musket down and went out and subdued them. That was how he told it: he went out and subdued them, and when he returned he and the girl became engaged to marry (p204)

So that Christmas Henry brought him home, into the house, and the demon looked up and saw the face he believed he had paid off and discharged twenty-eight years ago. (p213) he must have stood there on the front gallery that afternoon and waited for Henry and the friend Henry had been writing home about all fall to come up the drive, and that maybe after Henry wrote the name in the first letter Sutpen probably told himself it couldn't be, that there was a limit even to irony beyond which it became either just vicious but not fatal horseplay or harmless coincidence, since Father said that even Sutpen probably knew that nobody yet ever invented a name that somebody didn't own now or hadn't owned once: and they rode up at last and Henry said, 'Father, this is Charles' and he - " ("the demon," Shreve said) " - saw the face and knew . . . that he stood there at his own door, just as he had imagined, planned, designed, and sure enough and after fifty years the forlorn nameless and homeless lost child came to knock at it and no monkey-dressed nigger anywhere under the sun to come to the door and order the child away; and Father said that even then, even though he knew that Bon and Judith had never laid eyes on one another, he must have felt and heard the design - house, position, posterity and all - come down like it had been built out of smoke, making no sound, creating no rush of displaced air and not even leaving any debris. And he not calling it retribution, no sins of the father come home to roost; not even calling it bad luck, but just a mistake: (pp214-15)

and the next Christmas came and Henry and Bon came to Sutpen's Hundred again and now Sutpen saw that there was no help for it, that Judith was in love with Bon and whether Bon wanted revenge or was just caught and sunk and doomed to, it was all the same. So it seems that he sent for Henry that Christmas eve just before supper time (Father said that maybe by now, after his New Orleans trip, he had learned at last enough about women to know it wouldn't do any good to go to Judith first) and told Henry. And he knew what Henry would say and Henry said it and he took the lie from his son and Henry knew by his father taking the lie that what his father had told him was true: and Father said that he (Sutpen) probably knew what Henry would do and counted on Henry doing it because he still believed that it had been only a minor tactical mistake, and so he was like a skirmisher who is outnumbered but cannot retreat who believes that if he is just patient enough and clever enough and calm enough and alert enough he can get the enemy scattered and pick them off one by one. And Henry did it. And he (Sutpen) probably knew what Henry would do next too, that Henry would go to New Orleans to find out for himself. Then it was '61 and Sutpen knew what they would do now, not only what Henry would do but what he would force Bon to do; maybe (being a demon - though it would not require a demon to foresee war now) he even foresaw that Henry and Bon would join that student company at the University; (pp216-17)

Grandfather became colonel of the regiment the company was in until he got hurt at Pittsburg Landing (where Bon was wounded) . . . (but with no help, no fudging, on his part because it was him that carried Bon to the rear after Pittsburg Landing) (p217)

And he (Grandfather) didn't know what had happened: whether Sutpen had found out in some way that Henry had at last coerced his conscience into agreeing with him as his (Henry's) father had done thirty years ago, whether Judith perhaps had written her father that she had heard from Bon at last and what she and Bon intended to do, or if the four of them had just reached as one person that point where something had to be done, had to happen, he (Grandfather) didn't know. He just learned that one morning Sutpen had ridden up to Grandfather's old regiment's headquarters and asked and received permission to speak to Henry and did speak to him and then rode away again before midnight. (p222)

"And - ?" "Yes. Henry killed him" followed by the brief tears which ceased on the instant when they began, (p223)

Maybe he even delivered the first string of beads himself, and Father said maybe each of the ribbons afterward during the next three years while the girl matured fast like girls of that kind do; or anyway he would know and recognize each and every ribbon when he saw it on her even when she lied to him about where and how she got it, which she probably did not, . . . But Father said how Wash's heart was still quiet even after he saw the dress and spoke about it, probably only a little grave now and watching her secret defiant frightened face while she told him (before he had asked, maybe too insistent, too quick to volunteer it) that Miss Judith had given it to her, helped her to make it: . . . and Father said how that afternoon Grandfather rode out to see Sutpen about something and there was nobody in the front of the store and he was about to go out and go up to the house when he heard the voices from the back and he walked on toward them and so he overheard them before he could begin to not listen and before he could make them hear him calling Sutpen's name. . . . and Wash standing there, not cringing either, in that attitude dogged and quiet and not cringing, and Sutpen said, 'What about the dress?' and Grandfather said it was Sutpen's voice that was short and sharp: not Wash's; that Wash's voice was just flat and quiet, not abject: just patient and slow: 'I have knowed you for going on twenty years now. I aint never denied yit to do what you told me to do. And I'm a man past sixty. And she aint nothing but a fifteen-year-old gal.' and Sutpen said, 'Meaning that I'd harm the girl? I, a man as old as you are?' and Wash: 'If you was arra other man, I'd say you was as old as me. And old or no old, I wouldn't let her keep that dress nor nothing else that come from your hand. But you are different.' and Sutpen: 'How different?' and Grandfather said how Wash did not answer and that he called again now and neither of them heard them; and then Sutpen said: 'So that's why you're afraid of me?' and Wash said, 'I ain't afraid. Because you are brave. . . . That's where it's different. . . . And I know that whatever your hands tech, where hit's a regiment of men or a ignorant gal or just a hound dog, that you will make hit right.' (pp226-28)

So that Sunday came, . . . three years after he had suggested to Miss Rosa that they try it first and if it was a boy and lived, they would be married. It was before daylight and he was expecting his mare to foal to the black stallion, so when he left the house that morning Judith thought he was going to the stable, . . . Then about a week later they caught the nigger, the midwife, and she told how she didn't know that Wash was there at all that dawn, when she heard the horse and then Sutpen's feet and he came in and stood over the pallet where the girl and the baby were . . . and that he jerked the riding whip toward the pallet and said, 'Well? Damn your black hide: horse or mare?' and that she told him and that he stood there for a minute . . . and then he looked at the girl on the pallet again and said, 'Well, Milly; too bad you're not a mare too. Then I could give you a decent stall in the stable' and turned and went out. . . . she just heard Sutpen say, 'Stand back, Wash. Dont you touch me': and then Wash, his voice soft and hardly loud enough to reach her: 'I'm going to tech you, Kernel': and Sutpen again: 'Stand back, Wash!' sharp now, and then she heard the whip on Wash's face but she didn't know if she heard the scythe or not (pp228-30)

Then they rode up. He must have been listening to them as they came down the road, the dogs and the horses, and seen the lanterns since it was dark now. And Major de Spain who was sheriff then got down and saw the body, though he said he did not see Wash nor know that he was there until Wash spoke his name quietly from the window almost in his face . . . They just heard him moving inside the dark house, then they heard the granddaughter's voice, fretful and querulous: 'Who is it? Light the lamp, Grandpaw' then his voice: 'Hit wont need to light, honey. Hit wont take but a minute' . . . and now all the men there claimed that they heard the knife on both the neckbones, though de Spain didn't. He just said he knew that Wash had come out onto the gallery . . . he saw Wash stoop and rise again and now Wash was running toward him. Only he was running toward them all, de Spain said, running into the lanterns so that now they could see the scythe raised above his head, . . . making no sound, no outcry (pp233-34)