Absalom, Absalom! : Chapter-by-Chapter Chronology

- Shreve

- Shreve-Quentin

- Narrator

- Bon-Henry-Quentin-Shreve

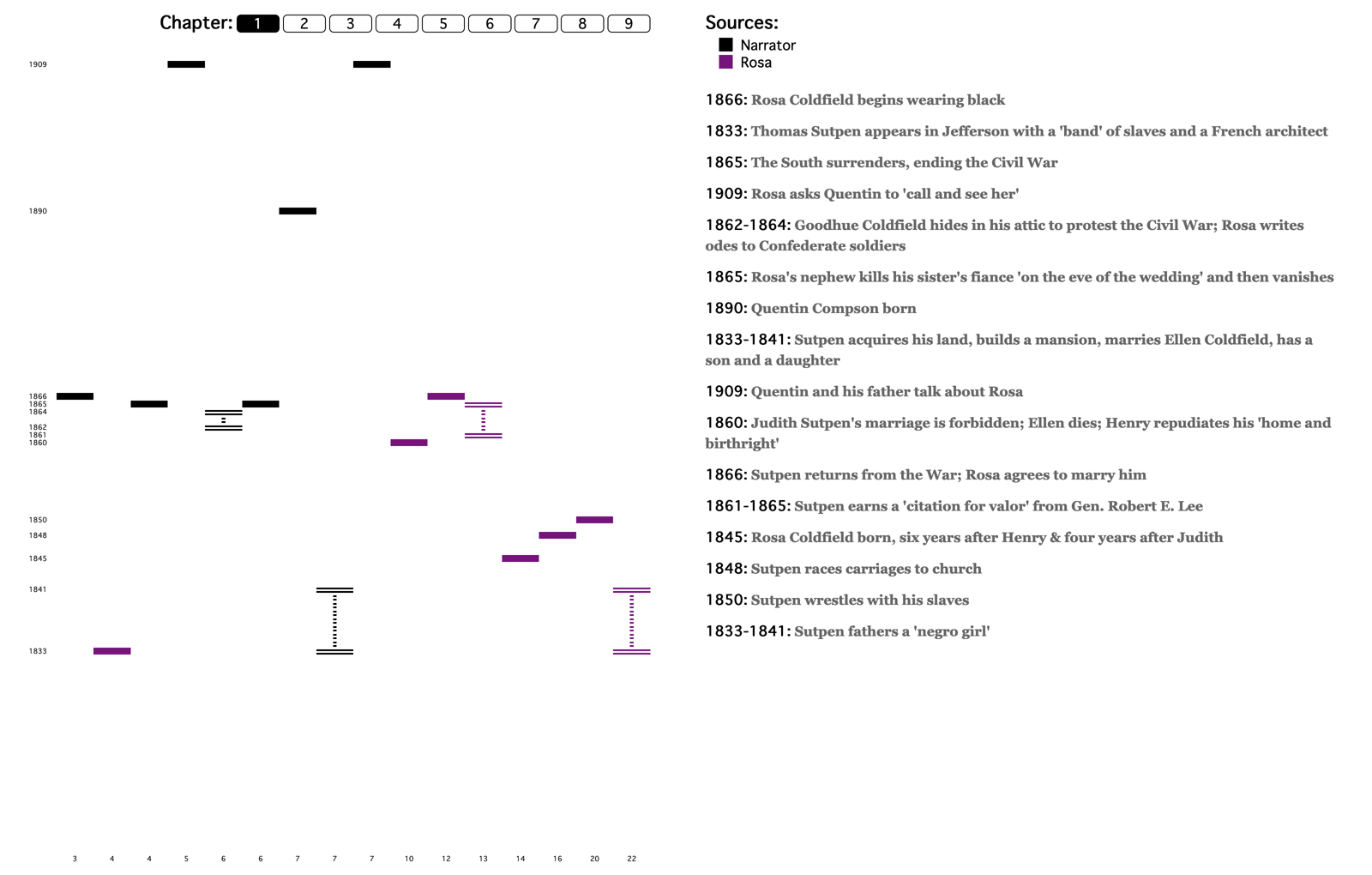

About Absalom, Absalom!: Chapter-by-Chapter ChronologyThe first section below explains why, given the fact that most editions of Absalom include a “Chronology” of significant events written by Faulkner himself, we designed this digital chronology for first-time readers. The second section, A Pair of Warnings, explains how both “significant” and “events” are conditional terms, not definitive claims. The third section describes how to use use our chronology. Rationale: The idea for this presentation grew from my experience teaching Absalom to college students who were motivated and experienced with other Faulkner texts but who, because of the novel’s extremely difficult prose style, found themselves reaching the end of a chapter or even the bottom of a page with no clear idea what is happening in the story. The novel’s very first reader was Faulkner’s editor, Hal Smith. As he worked through the manuscript Smith grew increasingly alarmed about this problem. Probably at his request, Faulkner created a map of Yoknapatawpha, a “Genealogy” of the major characters, and a “Chronology” listing 33 important events in the story that lies behind the novel’s narrative. Random House printed these explanatory materials at the end of the book, and they are still included in the Vintage International edition that my students were reading. I was reluctant, however, to point them to Faulkner’s Chronology for help keeping track of the plot of the story. Absalom unfolds with deliberate ambiguity and uncertainty through the accounts of five different story-tellers – a third-person narrator, Miss Rosa, Mr. Compson, Quentin and Shreve – who use a dozen more sources along with their own imaginations and personal prejudices to try to reconstruct the past that haunts the South. Their versions complement, complicate and contradict each other as the novel works toward what may be a dramatic epiphany about the past and its legacy at the end of the penultimate chapter. Consulting Faulkner’s Chronology before you’ve read the whole narrative, however, is like reading an inept detective fiction that identifies who done it less than halfway through the book: five of the Chronology’s first six items give away crucial plot points that the actual narrative withholds until it approaches the end. To give students an alternative way to get a grasp on the main events of the story, one that stays closer to the actual experience of reading the novel as that story is told and retold, Will Rourk and I in 2011 created a Flash-based, online prototype of this chapter-by-chapter chronology. Read each chapter first, I told my students, and then use the electronic chronology to clarify the main events disclosed in that chapter. That Flash-based version no longer works. This version of the chronology has been rebuilt by Doug Ross. And while it was designed with first-time readers in mind, I hope it might help even veteran ones discover new ways to engage the text. It certainly did that for me. Until I saw the graphs of the nine chapters, for instance, I hadn’t realized just how many significant events I had selected cluster around 1860-1866 – the era of the Civil War. While Faulkner’s story takes place across more than a century, 53 of the 126 events in this chronology (42%) occur within that six-year period. Sure, among its main cast members are a Confederate general, a colonel, a major, a lieutenant and a private – but the Union army is never seen, and there are almost no Northern characters at all. The story does intersect briefly, for example, with the Battle of Gettysburg. But it is by no means a “war story.” That epiphany at the end of Chapter 8 I mentioned is by far the book’s longest scene with a military setting, but the conflict it dramatizes, while unmistakably Southern, is not at all military, and its major characters are all wearing Confederate uniforms. Graphing the narrative helped me realize how powerfully, and how tragically, Absalom, Absalom! redefines the familiar phrase “brother against brother.” A Pair of Warnings. First caveat: this chronology consists of 126 events, between 8 and 16 per chapter. It includes almost all of the 33 in Faulkner’s Chronology, but adds many others that were chosen by me for their narrative and thematic significance. Another editor could have selected more, or fewer, or different events. I don’t claim my list is definitive, but rather – like each story-teller’s version of the story – an interpretive act. My self-imposed limit of 16 events per chapter is meant to keep each batch small enough to be manageable and useful to a first-time reader. A second caveat: with this novel the word event should always be in quotation marks. There is no “event” on these lists, or Faulkner’s for that matter, that we can say “really happened.” One of novel’s central themes is how the past can only be reconstructed, not lived firsthand, and so even the reliability of the book’s third-person narrator, who is looking back on the story a quarter century after its last event takes place, may be unreliable. It is up to each reader to decide which story-tellers, sources or events give us the best access to the past. For this reason, our chronology color-codes the specific narrator or narrative source for each event. Black icons are used, for example, to identify the third-person narrator’s contributions. Between 2 and 10 sources are responsible for the reconstructions in each chapter; they are identified at the top of each chapter’s page. Here are all 16 sources and their respective color codes:  (NOTE: hyphens and stripes are used when it seems a source is relying on and perhaps revising another source, such as when Mr. Compson in 1909 relays what his father, General Compson, told him years earlier. The composites “Quentin-Shreve” and “Shreve-Quentin” are our way of distinguishing which is actually speaking in those passages where the narrative says the two are in perfect agreement; the actual speaker is listed first.) Using the Chronology: Your first step in using the program is choosing the chapter you want to review by clicking on any of the 9 boxes at the top left of the page. Your choice will be highlighted in red, as Chapter 1 is here. All the following illustrations are from that chapter. Below you can see how that chapter’s 16 events are displayed on both the lefthand graph and the righthand list.  The list of Chapter 1 events on the righthand is sorted in the order of their appearance in the text, from page 3 to page 22 in the 2011 Vintage paperback. On the graph, the same events are located in both narrative and chronological order. The horizontal x-axis plots events from left to right as they occur in the text; the numbers below the axis are page numbers. The vertical y-axis indicates when an event occurs in time, from 1800 at the bottom up to 1910 at the top; the numbers to the left of the y-axis are dates. (NOTE: when you use the program on your computer or laptop, you may have to scroll down to see the earliest events on the graph or the events that occur later in a chapter on the righthand list.)

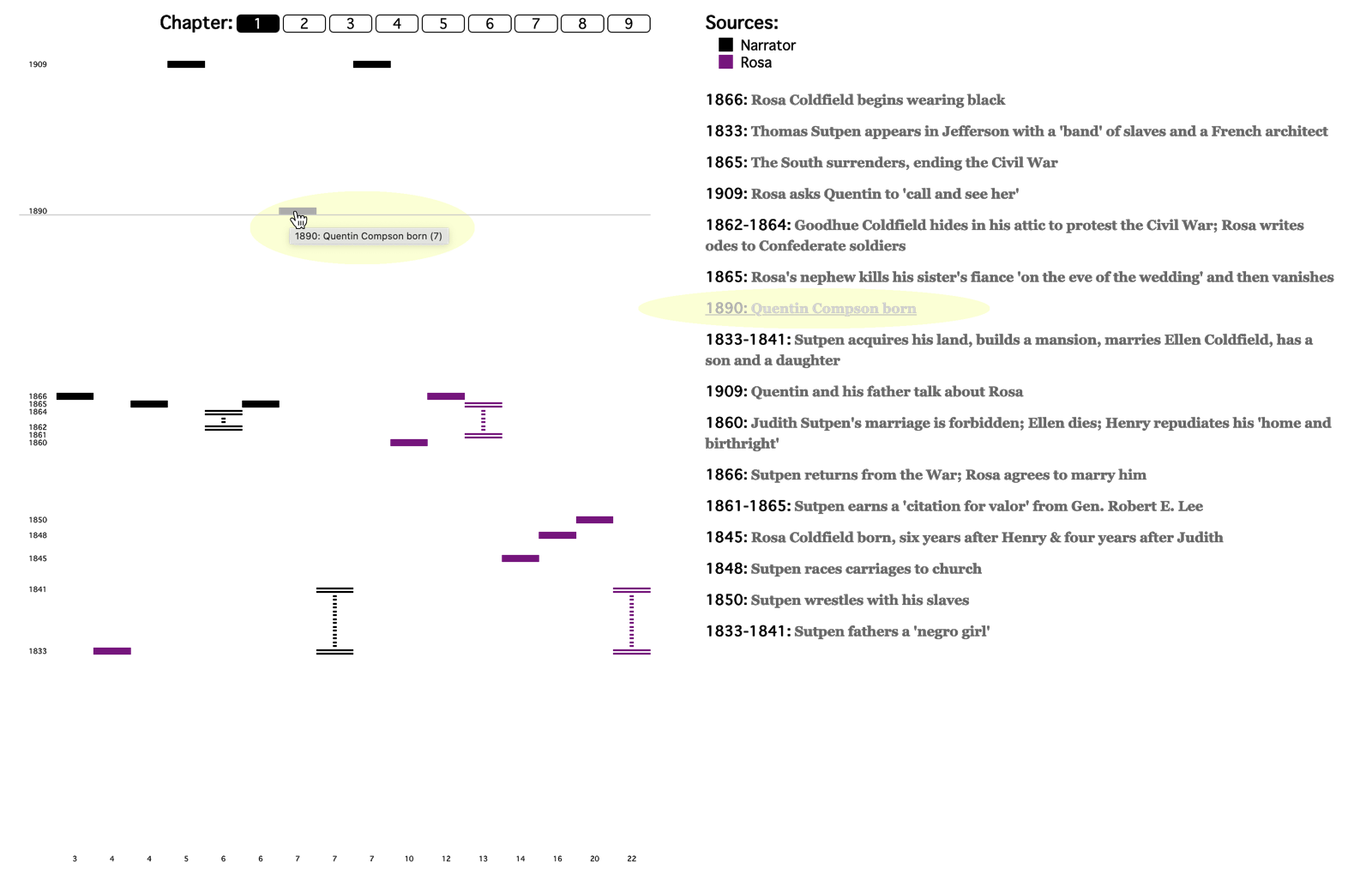

The icon in the example highlighted here is black, identifying the novel’s narrator as its source. It appears at the left of the x-axis and near the top of the y-axis – that is, early in the narrative but late in the story. The example also highlights what happens when you move your cursor over an icon: a brief description of the event itself as well as its date and page number pop up on the graph. The graph’s visualization of this information may prompt us to reflect on one of the central facts of this novel: that Quentin is present from the beginning of the narrative to its final page, yet is born only after almost all the story is in the past that Faulkner finds many ways to remind us “is never dead.” You can also see in this example how the graph and the list are interlinked: with your cursor over the icon, the position of the event on the list is indicated. Highlighted on the illustration below is the icon we use to plot multi-year events on the graph:

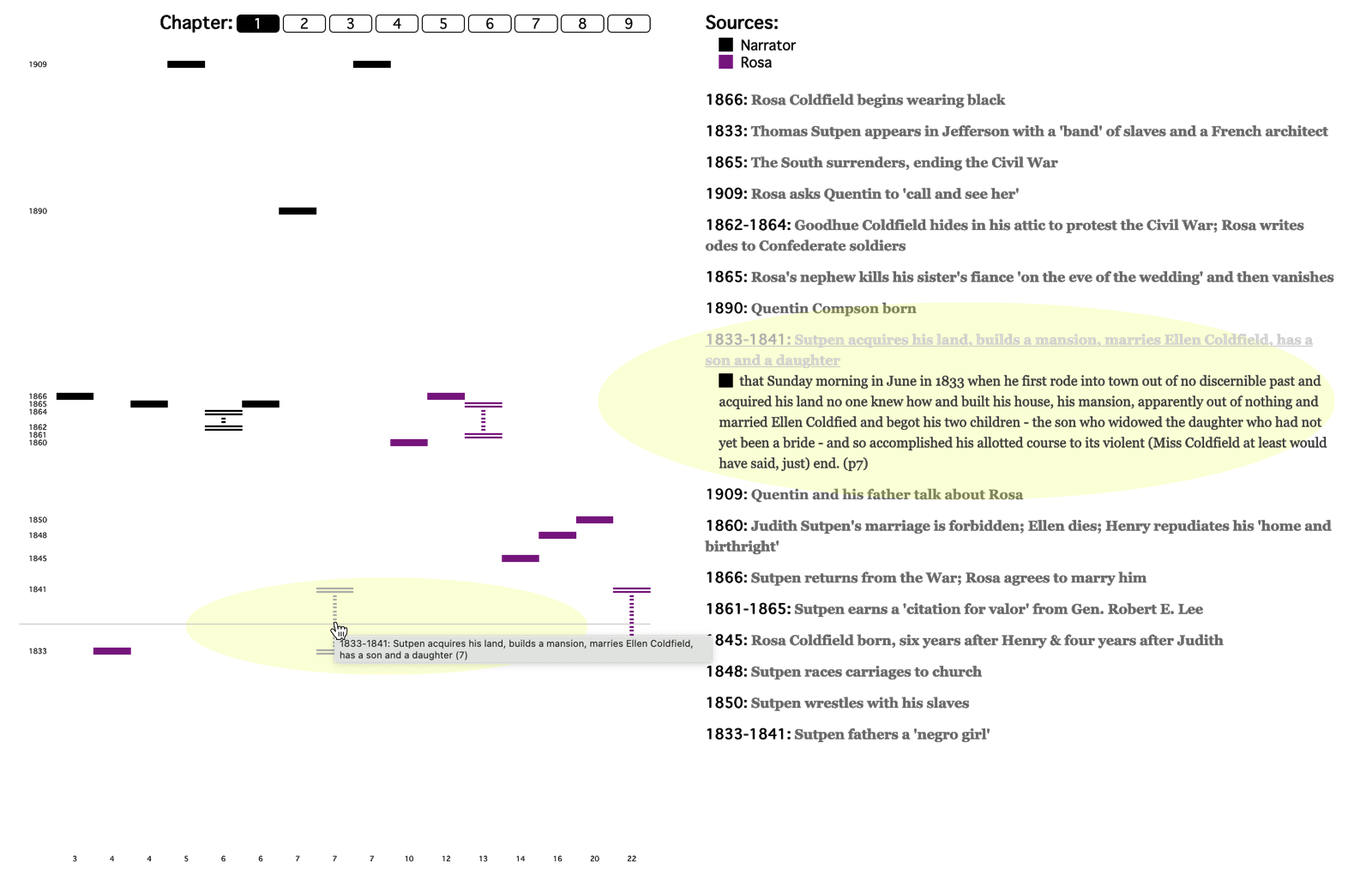

I wrote the descriptions of the events on graphs and list, but this illustration also shows what happens when you click on an graph icon or a list item: clicking expands the list entry to include the passage from Absalom where the event is first mentioned. This feature allows you to work back from our re-presentation of the novel to Faulkner’s actual text. That, of course, is what we hope this resource ultimately gives you: a means, not an end – a way to return to Absalom, Absalom! perhaps a bit readier to appreciate and understand it. – Stephen Railton For more on Faulkner, Hal Smith, and the published “Chronology,” see “Absalom, Absalom! Manuscripts Etc. and Absalom, Absalom! The Chronologies - but remember that Faulkner’s chronology includes a lot of spoilers! For more on the novel’s various sources, see The Narrative Sources of Absalom, Absalom! Citing this resource:

|

And Henry came in and the old man said 'They cannot marry because he is your brother' and Henry said 'You lie' like that, that quick: no space, no interval, no nothing between like when you press the button and get light in the room. And the old man just sat there, didn't even move and strike him and so Henry didn't say 'You lie' again because he knew now it was so; (p235)

grooming him herself, bringing him on by hand herself, washing and feeding and putting him to bed and giving him the candy and the toys and the other child's fun and diversion and needs in measured doses like medicine with her own hand: not because she had to, who could have hired a dozen or bought a hundred to do it for her with the money, the jack that he (the demon) had voluntarily surrendered, repudiated to balance his moral ledger; but like the millionaire who could have a hundred hostlers and handlers but who has just the one horse, the one maiden, the one moment, the one matching of heart and muscle and will with the one instant: and himself (the millionaire) patient in the overalls and the sweat and the stable muck, bringing him along to the moment when she should say 'He is your father. He cast you and me aside and denied you his name. Now go' and then sit down and let God finish it: pistol or knife or rack; destruction or grief or anguish: God to call the shot or turn the wheel. Jesus, you can almost see him: a little boy . . . he not even knowing maybe that he took it for granted that all kids didn't have fathers too and that getting snatched every day or so from whatever harmless pursuit in which you were not bothering anybody or even thinking about them, by someone because that someone was bigger than you, and being held for a minute or five minutes under a kind of busted water pipe of incomprehensible fury and fierce yearing and vindictiveness and jealous rage was a part of childhood which all mothers of children had received in turn from their mothers and from their mothers in turn from that Porto Rico or Haiti or wherever it was we all came from but none of us ever lived in:" (pp238-39)

Or maybe she was so busy grooming him that she never thought of the money now, who probably never had had much time to remember it or count it or wonder how much there was in the intervals of the hating and the being mad, and so all to check him up about the money would be the lawyer and he (Bon) probably learned that the first thing: . . . Sure, that's who it would be: the lawyer with his private mad female millionaire to farm . . . that lawyer who, with Bon's mother already plotting and planning him since before he could remember (and even if she didn't know it or whether she knew it or not or would have cared or not) for that day when he should be translated quick into so much rich and rotting dirt, had already been plowing and planting and harvesting him and the mother both as if he already was - that lawyer who maybe had the secret drawer in the secret safe and the secret paper in it, maybe a chart with colored pins stuck into it like generals have in campaigns, . . . and maybe here with the date too: Daughter and you could maybe even have seen the question mark after it and the other words even: daughter? daughter? daughter? (pp240-41)

(he would have known about the octoroon and the left handed marriage long before the mother did even if it had been any secret; maybe he even had a spy in the bedroom like he seems to have had in Sutpen's; maybe he even planted her, said to himself like you do about a dog: He is beginning to ramble. He needs a block. Not a tether: just a light block of some sort so he cant get inside of anything that might have a fence around it) (p242)

So he went away. He went away to school at the age of twenty-eight. And he wouldn't know or care about that either: which of them - mother or lawyer - it was who decided he should go to school nor why, because he had known all the time that his mother was up to something and that the lawyer was up to something, and he didn't care enough about what either of them was to try to find out, (p246) and one night he walked up the gangplank . . . And who knows what thinking . . . And maybe the letter itself right there under his feet, somewhere in the darkness beneath the deck on which he stood - the letter addressed not to Thomas Sutpen at Sutpen's Hundred but to Henry Sutpen, Esquire, in Residence at the University of Mississippi, near Oxford, Mississippi: and one day Henry showed it to him and there was no gentle spreading glow but a flash, a glare (who not only had no visible father but found himself to be, even in infancy, enclosed by an unsleeping cabal bent apparently on teaching him that he had never had, that his mother had emerged from a sojourn in limbo, from that state of blessed amnesia in which the weak senses can take refuge from the godless dark forces and powers which weak human flesh cannot stand, to wake pregnant, shrieking and screaming and thrashing, not against the ruthless agony of labor but in protest against the outrage of her swelling loins; that he had been fathered on her not through that natural process but had been blotted onto and out of her body by the old infernal immortal male principle of all unbridled terror and darkness) in which he stood looking at the innocent face of the youth almost ten years his junior, while one part of him said My brow my skill my jaw my hands and the other said Wait. Wait. You cant know yet. You cannot know whether what you see is what you are looking at or what you are believing. Wait. Wait. - the letter which he - - " it was not Bon he meant now, yet again Quentin seemed to comprehend without difficulty or effort whom he meant " - - wrote maybe as soon as he finished that last entry in the record, into the daughter? daughter? daughter? while he thought By all means he must not know now, must not be told before he can get there and he and the daughter - not remembering anything about young love from his own youth and would not have believed it if he had, yet willing to use that too as he would have used courage and pride, thinking not of any hushed wild importunate blood and light hands hungry for touching, but of the fact that this Oxford and this Sutpen's Hundred were only a day's ride apart and Henry already established in the University and so maybe for once in his life the lawyer even believed in God: (pp250-51)

then (Bon) agreeing at last, saying at last, 'All right. I'll come home with you for Christmas' . . . Because he know exactly what he wanted; it was just the saying of it - the physical touch even though in secret, hidden - the living touch of that flesh warmed before he was born by the same blood which it had bequeathed to him to warm his own flesh with, . . . And went into the house: and maybe somebody looking at him would have seen on his face an expression a good deal like the one - that proffering with humility yet with pride too, of complete surrender - which he had used to see on Henry's face, and maybe he telling himself I not only dont know what it is I want but apparently I am a good deal younger than I thought also: and saw face to face the man who might be his father, and nothing happened - . . . and if so, why? why? thinking But why? Why? since he wanted so little, could have understood if the other had wanted the other to be in secret, would have been quick and glad to let it be in secret even if he could not have understood why, thinking in the middle of this My God, I am young, young, and I didn't even know it; they didn't even tell me, that I was young, feeling that same despair and shame like when you have to watch your father fail in physical courage, thinking It should have been me that failed; me, I, not he who stemmed from that blood which we both bear before it could have become corrupt and tainted by whatever it was in Mother's that he could not brook. - " (pp255-57)

Four of them there, in that room in New Orleans in 1860, just as in a sense there were four of them here in this tomblike room in Massachusetts in 1910. And Bon may have, probably did, take Henry to call on the octoroon mistress and the child, as Mr Compson said, though neither Shreve nor Quentin believed that the visit affected Henry as Mr Compson seemed to think. In fact Quentin did not even tell Shreve what his father had said about the visit. Perhaps Quentin himself had not been listening when Mr Compson related (recreated?) it that evening at home; perhaps at that moment on the gallery in the hot September twilight Quentin took that in stride without even hearing it just as Shreve would have, since both he and Shreve believed - and were probably right in this too - that the octoroon and the child would have been to Henry only something else about Bon to be, not envied but aped if that had been possible, if there had been time and peace to ape it in - peace not between men of the same race and nation but peace between two young embattled spirits and the incontrovertible fact which embattled them, since neither Henry and Bon, any more than Quentin and Shreve, were the first young men to believe (or at least apparently act on the assumption) that wars were sometimes created for the sole aim of settling youth's private difficulties and discontents. (pp268-69)

("Listen," Shreve said, cried. "It would be while he would be lying in a bedroom of that private house in Corinth after Pittsburg Landing while his shoulder got well two years later and the letter from the octoroon (maybe even the one that contained the photograph of her and the child) finally overtaking him" (p271)

and telling him that the lawyer had departed for Texas or Mexico or whomewhere at last and that she (the octoroon) could not find his mother either and so without doubt the lawyer had murdered her before he stole the money, since it would be just like both of them to flee or get themselves killed without providing for her at all. (p271)

Then it was Christmas again, then 1861, and they hadn't heard from Judith because Judith didn't know for sure where they were because Henry wouldn't let Bon write to her yet; then they heard about the company, the University Grays, organising up at Oxford and maybe they had been waiting for that. So they took the steamboat North again, and more gayety and excitement on the boat now than Christmas even, like it always is when a war starts, before the scene gets cluttered up with bad food and wounded soldiers and widows and orphans, and them taking no part in it now either but standing at the rail again above the churning water, and maybe it would be two or three days, then Henry said suddenly, cried suddenly: 'But kings have done it! Even dukes! There was that Lorraine duke named John something that married his sister. The Pope excommunicated him but it didn't hurt! It didn't hurt! They were still husband and wife. They were still alive. They still loved!' then again, loud, fast: 'But you will have to wait! You will have to give me time! Maybe the war will settle it and we won't need to!' And maybe this was one place where your old man was right: and they rode into Oxford without touching Sutpen's Hundred and signed the company roster and then hid somewhere to wait, (p273)

and Henry let Bon write Judith one letter; they would send it by hand, by a nigger that would steal into the quarters by night and give it to Judith's maid, and Judith sent the picture in the metal case (p273)

Then it was Shiloh, the second day and the lost battle and the brigade falling back from Pittsburg Landing - And listen," Shreve cried; "wait, now; wait!" (glaring at Quentin, panting himself, as if he had to supply his shade not only with a cue but with breath to obey it in): "Because your old man was wrong here, too! He said it was Bon who was wounded, but it wasn't. Because who told him? Who told Sutpen, or your grandfather either, which of them it was who was hit? Sutpen didn't know because he wasn't there, and your grandfather wasn't there either because that was where he was hit too, where he lost his arm. So who told them? Not Henry, because his father never saw Henry but that one time and maybe they never had time to talk about wounds and besides to talk about wounds in the Confederate army in 1865 would be like coal miners talking about soot; and not Bon, because Sutpen never saw him at all because he was dead; - it was not Bon, it was Henry; Bon that found Henry at last and stooped to pick him up and Henry fought back, struggled, saying, 'Let be! Let me die! I wont have to know it then' and Bon said, 'So you do want me to go back to her' and Henry lay there struggling and panting, with the sweat on his face and his teeth bloody inside his chewed lip, and Bon said, 'Say you do want me to go back to her. Maybe then I wont do it. Say it' and Henry lay there struggling, with the fresh red staining through his shirt and his teeth showing and the sweat on his face until Bon held his arms and lifted him onto his back - " (p275)

Then one day (he was an officer; he would have known, heard, that Lee had detached some troops and sent them down to reinforce them; perhaps he even knew the names and numbers of the regiments before they arrived) he saw Sutpen. Maybe that first time Sutpen actually did not see him, maybe that first time he could tell himself, 'That was why; he didn't see me,' so that he had to put himself in Sutpen's way, make his chance and situation. Then for the second time he looked at the expressionless and rocklike face, at the pale boring eyes in which there was no flicker, nothing, the face in which he saw his own features, in which he saw recognition, and that was all. . . . And maybe it was that same night or maybe a night a week later . . . that Bon said, 'Henry' and said, 'It wont be much longer now and then there wont be anything left; . . .' And then Henry would begin to say 'Thank God. Thank God' panting and saying 'Thank God,' saying 'Dont try to explain it. Just do it' and Bon: 'You authorise me? As her brother you give me permission?' and Henry: 'Brother? Brother? You are the oldest: why do you ask me?' and Bon: 'No. He has never acknowledged me. He just warned me. You are the brother and the son. Do I have your permission, Henry?' and Henry: 'Write. Write. Write.' So Bon wrote the letter, after the four years, and Henry read it and sent it off. (pp278-79)

Then one night they had stopped again since Sherman had stopped again, and an orderly came along the bivouac line and found Henry at last and said, 'Sutpen, the colonel wants you in his tent.' (p279) Yes. I have decided. Brother or not, I have decided. I will. I will. - He must not marry her, Henry. - Yes. I said Yes at first, but I was not decided then. I didn't let him. But now I have had four years to decide in. I will. I am going to. - He must not marry her, Henry. His mother's father told me that her mother had been a Spanish woman. I believed him; it was not until after he was born that I found out that his mother was part negro. (p283)

didn't tell you in so many words anymore than she told you in so many words how she had been in the room that day when they brought Bon's body in and Judith took from his pocket the metal case she had given him with her picture in it, (p280) and maybe they left together and rode side by side dodging Yankee patrols all the way back to Mississippi and right up to that gate; side by side and it only then that one of them ever rode ahead or dropped behind and that when Henry spurred ahead and turned his horse to face Bon and took out the pistol; and Judith and Clytie heard the shot, and maybe Wash Jones was hanging around somewhere in the back yard and so he was there to help Clytie and Judith carry him into the house and lay him on the bed, and Wash went to town to tell the Aunt Rosa and the Aunt Rosa comes boiling out that afternoon and finds Judith standing without a tear before the closed door, holding the metal case she had given him with her picture in it but that it didn't have her picture in it now but that of the octoroon and the kid (p286)